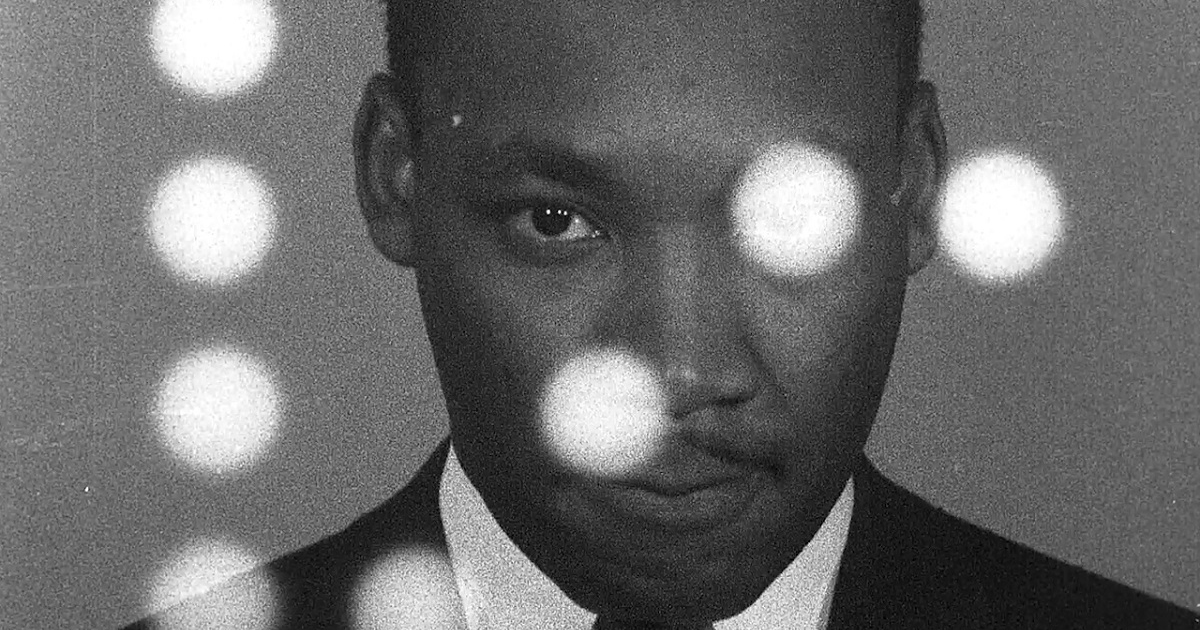

Much of what we think we know about the Black Panthers has been misrepresented, misdirected and underreported for decades. The murder of one of its leaders in the burning heat of the Civil Rights movement in 1969 should have been a turning point, but instead the party was branded a militant terrorist group. It’s taken over half a century for the truth to reach the screen.

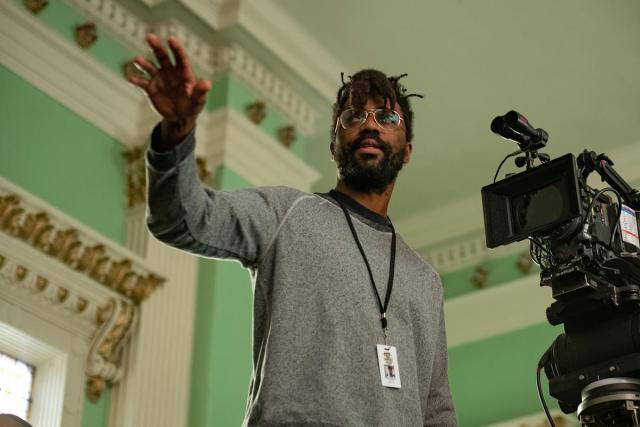

“I was shocked,” says cinematographer Sean Bobbitt, BSC on reading the script for Judas And The Black Messiah. “I felt very guilty about not knowing that story. It spurred me on to do my own research and to learn more.”

Director Shaka King co-wrote the script with Will Berson based on a story by King, Berson and Kenny and Keith Lucas. The film is an unconventional biopic of Fred Hampton (Daniel Kaluuya), chairman of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party. In 1969, Hampton united a Rainbow Coalition of underrepresented activists and the poor, which included Puerto Rican group the Young Lords and the white Young Patriots, to fight for equality and political empowerment.

The events leading up to Hampton’s assassination are harnessed to the story of William O’Neal (LaKeith Stanfield), a petty criminal, FBI informant and “Judas,” in much the same way the fate of the outlaw Jesse James was yoked to the coward Robert Ford in Andrew Dominik’s 2007 revisionist Western.

“For Shaka, it was crucial that this film feel intimate. Although Hampton and O’Neal have different forces driving them through the story — one is a hero and the other is a villain — at the same time you need to have sympathy for both. It was that balance inherent in the script which was fascinating.”

— Sean Bobbitt, Director of Photography, “Judas and the Black Messiah”

“It shocks me that people are pigeonholing Daniel as a supporting actor,” Bobbitt says. “The whole idea is that their characters are equals moving through this world. It was very important for Shaka to get that balance right and to make them as human and three dimensional as possible. As odious as O’Neal is, we are still sympathetic to him and the changes he goes through. At one point, he has his fist raised and is chanting. He is a Panther. But he is a complex character. An enigma.”

Opening Shots

The film opens with a long single Steadicam shot on a street at night as we follow O’Neal into a bar, ostensibly to round up suspects (actually to steal a car) and reveal himself to be an FBI agent.

“Shaka had this in his mind from the beginning to grab the audience,” Bobbitt says. “That low angle sweeping coat in the wind might suggest a superhero movie or a classic noir thriller. We’re trying to throw the audience off and to set a tone with constant movement throughout. One of the themes the movie has is a constant progression in it towards an inevitable and horrific end.”

A red neon sign gives the scene a very distinct vibe. Part of that is for shock, he says. Red is a very emotive color — but it’s also Bobbitt’s aim to introduce his concept for mixed light and colors.

“If you look down the street [in that shot] there are lighting instruments hidden all over the place — some are blue, some orange, some are street light gold mixed with the level of darkness. We’re trying to set the tone for how the film is going to work,” Bobbitt notes.

King had collected hundreds of historical photos of the West Side of Chicago in the late 1960s that became the key to the film’s visual approach.

Color and Lighting

“Some fantastic black and white, others wonderful Ektachrome and Kodachrome where you get those very crushed blacks and very strong primaries,” Bobbitt details. “Working with production designer Sam Lisenco, that was the basis from which everything moved. It was trying to induce a feel of period through those colors.”

Lisenco’s own research included materials made available through the Freedom of Information Act, including FBI files on the Black Panthers and archival materials from museums. The idea was to create a realistic period portrait of Chicago, including putting garbage on the streets, using burnt out cars, and trying to do justice to the economic levels within the municipalities in the late 1960s.

“There are, of course, elements of dramatic license, but it’s ostensibly a true story so we didn’t want it to feel documentary,” Bobbitt says. “We wanted it to feel like a film that might have been made in the 1960s. From that comes the composition and movement of the cameras.”

Scenes featuring the FBI are monochrome and flatter, whereas when we are with the Panthers the light is imbued with lush greens, reds and warm oranges. These scenes are also staged with a stronger mix of color temperature and contrast to create depth.

“As we scouted the film’s locations in Cleveland, we kept seeing this color green — ‘panther green’ we called it,” Bobbitt recounts. “It first hit us in the Panther’s headquarters in the upstairs room and it was something we were initially not sure about — but it just suddenly felt right to all of us. We kept finding that color in different locations — in the interrogation cell where O’Neal meets the FBI and also in the church where Fred delivers a great speech on his return from jail.”

“There are, of course, elements of dramatic license, but it’s ostensibly a true story so we didn’t want it to feel documentary. We wanted it to feel like a film that might have been made in the 1960s. From that comes the composition and movement of the cameras.”

— Sean Bobbitt, Director of Photography, “Judas and the Black Messiah”

The culmination of all this for Bobbitt is in the grade. “I’m fortunate to work with Tom Poole in Company 3 who, I think, is the best in the world. He has an eye for detail. He created these unique looks that would push the reds, greens and blues so that you get a stunning visual continuity.”

Films such as Michael Mann’s Heat and the Muhammad Ali documentary When We Were Kings were screened to help build a visual lexicon. Bobbitt drew on his past experience in reportage for some scenes, notably a demonstration outside the Chicago Police department, which was shot handheld.

Composing for Widescreen

“Shaka was very keen we find very strong frames that the action occurs in front of and then picking up the little bits we need to tell the story,” says Bobbitt. “It’s all single camera. There’s no coverage. I don’t allow that word to be used on set. It is in the tradition of ‘60s and ‘70s auteurs filmmakers.”

This led the DP toward the Arri Alexa LF and Mini LF cameras, which he tested in London. “I always push toward shooting in a widescreen 2.40 aspect ratio when I can,” he says. “It works on several different levels. The first is perceived production value. When an audience is in the cinema, it is the letter box frame that conditions them to think this is a big film. Their expectation is that it’s going to be epic. You get that for free.

“Then, as an operator you have so much more to compose with within that frame. Even the smallest moves are so much more dynamic because of the amount of information you have in the frame.

“In this case, it’s an ensemble cast and with that wide frame you can get fantastic compositions where you can comfortably fit seven or eight people in the frame. Since Shaka’s desire was to find these strong frames, it’s a format that gives you so much more opportunity to do that.

“The other advantage is that you get a great sense of scale and at the same time the ability to create remarkable intimacy. Even a mid-shot, because of the size of the sensor and the way the lenses work, your focus drops off quite dramatically so you’re able to pull your actors out of the background and pull the audience’s eyes specifically to them, but you still have enough interest in the background so you know where they are.”

Bobbitt uses the close-up sparingly in this film. “If you do it all the time, the value is lost,” he says. “If you work at mids and wides all the time, then when you do come in close it’s a real punctuation point. When you are in there that close you also have a remarkable bokeh. All around it was a win-win on this film and on pretty much every film I’ve ever shot.”

With a significant number of nighttime exteriors and others set in low light, together with dark skin tones, Bobbitt needed lenses that were fast enough without having to push the ASA out of the camera too high or to add huge amounts of lighting.

Shooting in Low Light

“That’s why we didn’t shoot anamorphic,” he says. “The amount of light needed would have been prohibitive. We went with ARRI DNA LF lenses. They have a softness to them and a lot of the characteristics of the older anamorphics, but with a much faster lens [to shoot at lower light levels]. I spent a lot of time on the locations looking at the available light that we could or can’t use or needed to augment.”

One dialogue scene is set in a car when it is raining outside. The camera has to view 360 degrees around the inside, with Bobbitt careful to keep the mix of color temperature and backlit light through the raindrops on the car windows. “I always work from premise that if I can do it with one light, I’ll do it with one light. In this case, we couldn’t. It was more interesting with more light,” he explains.

“Overall in the film, we put little bare bulbs in the background and little Fresnels to give us out of focus hotspots. Hopefully in every frame at night, somewhere in the distance there is a hotspot. That also helps with exposure. If you have a hotspot, then audiences are more willing to accept under exposure on the faces. If the frame is completely dark it goes to mush, so those little hotspots are always something I look for in composition and exposure.”

While J. Edgar Hoover (Martin Sheen) is portrayed as omnipotent, almost pure evil, King doesn’t judge the other characters. This includes Jesse Plemmons’ FBI goon, who has qualms about the Bureau’s actions and, notably, O’Neal, who is depicted as much a victim of the system as Hampton, even as he betrays his trust.

“For Shaka, it was crucial that this film feel intimate,” Bobbitt says. “Although Hampton and O’Neal have different forces driving them through the story — one is a hero and the other is a villain — at the same time, you need to have sympathy for both. It was that balance inherent in the script which was fascinating.”

There seems to have been some criticism of the movie that irks Bobbitt, criticism that it doesn’t show Hampton and O’Neal interacting together more often.

“That’s because they weren’t friends,” says Bobbitt. “Shaka was working very closely with Fred Hampton, Jr., (Hampton’s son) and Deborah (his fiancée, who is played in the film by Dominique Fishback) and they told him that O’Neal was not a friend and that he and Hampton never spent time together. They were never together in a room alone. O’Neal worked his way up through the Panthers. Fred must have had some respect for him, because he moved up through the cadre, but he was never Hampton’s bodyguard. So in some ways, the drama of the story is dictated by the reality and the drama has its hands tied by the reality. I still have immense sympathy for both characters and the key part of that is the performances by Daniel and LaKeith, which are outstanding.”

War Zone to Hollywood

Born in Texas, Bobbitt has lived overseas for most of his life and in the 1960s and 1970s he was in Saudi Arabia (Bobbitt’s father was an oil executive), and then in public school in England.

In the UK at that time, Bobbitt says, the Panthers were treated more as a style icon than a serious political movement. “At school, I was learning about the Kings and Queens of England. The events in the U.S. really passed me by.”

Bobbitt spent his first ten years in the industry filming in conflict zones like Beirut, Iraq and the Philippines as a freelance cameraman for American news networks. He didn’t shoot his first feature (Michael Winterbottom’s Wonderland) until age 39.

“I always push toward shooting in a widescreen 2.40 aspect ratio when I can. It works on several different levels. The first is perceived production value. When an audience is in the cinema, it is the letter box frame that conditions them to think this is a big film. Their expectation is that it’s going to be epic. You get that for free. Then, as an operator you have so much more to compose with within that frame. Even the smallest moves are so much more dynamic because of the amount of information you have in the frame.”

— Sean Bobbitt, Director of Photography, “Judas and the Black Messiah”

A long-running collaboration with director Steve McQueen, including on Hunger, Shame, 12 Years a Slave and Widows cemented his reputation. He has also photographed The Place Beyond the Pines, Spike Lee’s Oldboy and Queen of Katwe for Mira Nair.

It was King who reached out to Bobbitt and arranged a meeting over tea in New York where the DP was grading The Courier.

“It was Shaka’s passion about the project and the knowledge and research he had done which got my attention,” Bobbitt says. “Within 10 minutes, I knew this was a film I wanted to do.”

Bobbitt says he had no acumen for or interest in photography until after university, when desperation led him to seek work at a production company in the UK. That led him to working in conflict zones for news and documentaries and learning to film on the job.

“Everything I do is informed by my earlier experience as a cameraman,” he says. “[With news] the story you are telling is often complex but can only be a minute and half long. It can’t be wallpaper.”

Covering war zones with just a sound recordist was a risky business. Death was never far away. “It’s the fear that keeps you alive, but you have to control it,” says Bobbitt. “It’s a constant risk assessment. On my first day in Lebanon, which was the first element of conflict I’d ever seen in my life, I remember an experienced cameraman telling me that the shot worth dying for has never been taken. I didn’t understand what he meant until about 15 minutes later. Then I understood. No one cares if you’re killed or injured. You are just collateral damage. Having said that, you still had a job to do.”

After nine years, he quit. “I knew that when I reached a point when I stopped crying at the horrors, — when I was inured to it — then it was time to do something different. It’s held me in good stead. I don’t get very pressured on a set.”

Now Does Hollywood Understand?

A Hampton biopic has been knocking around town for years, but it took the door-prizing muscle of producer Ryan Coogler to finally get the script, previously titled Jesus Was My Homeboy, to get it made. Despite the pressure to tell more stories relevant to BAME communities, it seemed that it was still a struggle to get a studio on board.

“I was under the impression that if you make a movie about a Black Panther, produced by the director of Black Panther, which made a billion dollars, starring two of the best actors of our generation, and you have a producer and co-financer in Charles King, who is willing to put up half the budget, it’s going to be a bidding war. That was not the case,” Shaka King told Variety.

“I don’t see a tremendous difference between how Hollywood interacts with Black storytellers and Black art as commerce,” King added. “It moves in waves. I don’t think there’s been a bone beat, spiritual makeover in Hollywood.”