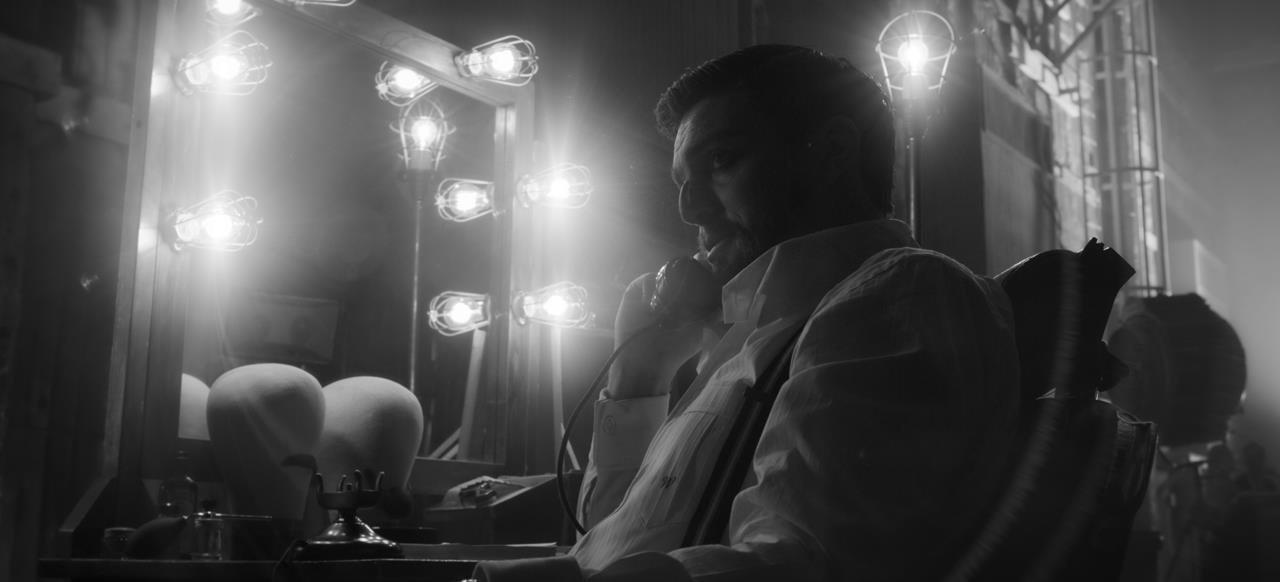

Mank, David Fincher’s period piece set in 1930s Hollywood, has a lot on its mind, from the workings of the studio system and the authorship of Citizen Kane to the influence of mass media on politics and the latter-day phenomenon of “fake news.” It’s no surprise that Mank features VFX shots — matte paintings, rear-projection work, and even a moonlight menagerie — that remake old Hollywood (and Hearst’s famed San Simeon estate) in loving detail, but the feature also painstakingly recreates the look of old celluloid, treating digitally captured images with some of the imperfections of 35mm film.

As is typically the case, Fincher himself shouldered overall VFX supervisor responsibilities while co-producer Peter Mavromates, a key member of his crew since the 1990s, managed the VFX budget, schedule and assignments. Mank was captured at 8K with RED Helium cameras (special monochrome-only sensors translated into slightly higher resolution and increased dynamic range) and VFX were finished at 6K but framed for a 5K center extraction, which was scaled to 4K for delivery to Netflix.

NAB Amplify asked Mavromates about making Mank, including working in black-and-white, executing old-school techniques with 21st-century technology, and finishing the show as the COVID lockdown hit.

NAB Amplify: The period-accurate visual effects shots in Mank are reminiscent of Zodiac [2007], with its amazing recreation of old San Francisco cityscapes and overhead shots. Zodiac was also one of the first truly tapeless feature film workflows. It’s amazing how many envelopes you have been pushing over so many different projects.

Peter Mavromates: David is impatient that way. He always wants to play with something new.

NABA: Is it correct to say that he is the uncredited VFX supervisor on his films, and you’re in the VFX producer’s role?

PM: Yeah, that’s correct. On the major stuff, he and I will talk about who the vendors are. But on a lot of the lesser stuff — what we call body-and-fender work — I’m doling that out and assigning it, managing that whole flow.

NABA: On Mank, was there a lot of major work or a lot of body-and-fender work — or was it a mix of the two?

PM: There’s always a lot of body-and-fender work, as David comes in every day trying to make everything better, and sometimes that means going in and tweaking something in the frame. Ever since everything became digital, from Panic Room forward, it’s become way easier to go in and fix something. We have a small team of VFX artists in-house, so a lot of that work doesn’t even have to get sent somewhere.

NABA: I understand Fincher has his own post facility?

PM: It’s funny when people describe it as a facility, which implies a business entity. It’s basically our post crew. We have one in-house compositor and two supporting VFX artists to do stabilizing and retouching. We can push a lot of shots through them. And the compositor does occasionally get some big sequences. The election-eve mindscape with all the blurry dissolves and superimpositions was done by the in-house compositor, Christopher Doulgeris. Our editor, Kirk Baxter, cut a structure for it and then we handed it off to Christopher and told him to go drop some acid then smush it all together.

NABA: Artemple just put out a VFX breakdown showing its work, including a simulated crane shot for the party scene in Hearst Castle showing these massive chandeliers that they created overhead. What goes into designing a shot like that — coordinating between the camera department, production design, what the director has in his head, and what the visual effects artists have to execute?

PM: In that particular case the art department supplied chandelier designs, and obviously we prefer that. When the shots are planned in advance, we’ll take advantage of Don Burt and his production design team. Every once in a while, something comes up in post, after the fact, and we may not have that luxury. We really take our cues from David.

NABA: What about the recreation of the exterior of Hearst Castle, with the array of caged animals that we see after Mank follows Marion Davies [Amanda Seyfried] out of the birthday party?

PM: We needed animals for three scenes and asked ILM to help. They populated the grounds with monkeys — and provided the monkey cage, as well — elephants, a zebra, and giraffes. These shots, along with the night San Simeon matte paintings from Artemple at the fountain scene that ends the sequence, are as close as we come to evoking Xanadu from Citizen Kane. This is a case of David making VFX choices on set and then passing the baton to the masters for their handiwork. I think the only animal we had ever done was a hummingbird in Benjamin Button, so we were a bit intimidated. To ILM, no doubt, it was just a walk in the park. They did the research to design the monkey cage and offered David tons of images to choose cage style, type of monkeys, and type of elephants. It was rather painless.

NABA: And there’s that other great scene inside the car that Sara is driving with Mank on Wilshire Boulevard. The city outside the car is a period-accurate digital environment created by Territory Studios that was displayed on screens on set, so the scene could be captured in camera.

PM: One of Territory’s artists came to L.A. and spent most of their time driving up and down Wilshire and doing their homework. I realized, “This is kind of embarrassing. These Brits know more about Wilshire Boulevard than anybody I know.” They obviously enjoy their work, and it was clear they were having fun doing it.

NABA: Do you have a Rolodex full of people that you work with, so you can quickly match jobs to vendors?

PM: We do have a lot of repeat offenders. I know them well and why they’re good. For instance, we do a lot of lens flares and we’ve done them so much with Savage VFX in Pittsburgh that that’s who’s going to get the lens flares. Ollin VFX in Mexico City gets a lot of the trickier stuff, since they’re really good problem-solvers. Wei Zheng at Artemple, that’s David’s matte painter. And sometimes Savage VFX. [Savage VFX Supervisor James Pastorius] did the matte paintings at the Upton Sinclair speech.

NABA: How did you balance a desire for period accuracy with a creative, stylized vision that draws on Citizen Kane and old-Hollywood visual tropes? Where did you decide, photorealism aside, in favor of artistic license and artistic merit?

PM: In many ways we used old techniques with new tools, which gave us more power. One example of that would be the LED screens [in the driving sequence], which are basically the modern version of rear projection. Somebody in 1939 could have shot that scene the same way, though they may not have been as successful, because they didn’t have all the tools to dial everything in as well as we did. Another example is that montage sequence Christopher did that I mentioned earlier, on election eve. Certainly Linwood Dunn [an optical-printing pioneer who worked closely with Orson Welles on special effects for Citizen Kane] would have been able to do something like that, but he wouldn’t have had the tools to re-render and modify and do dozens of versions of it. But you could have done a similar sequence in 1939. The matte paintings were matte paintings in the silent era as well. Sure, they were done differently. Some of them were literally painted on a piece of glass that was in front of the camera on the set. But Artemple had more powerful tools, obviously, than they had in the 1930s.

NABA: You can also do these effects without a generational decrease in quality from running through the optical printer multiple times.

PM: That’s correct. And we added that that generational loss after the fact. We amped up the grain any time there was what would be considered a traditional optical.

NABA: It’s a subtle effect.

PM: It’s tricky because we live in a world where people are watching it on a four-inch screen and an 85-inch screen and everything in between. You can’t serve all those different sizes, so we assumed somewhere between a 32- and an 85-inch screen and tried to hit the sweet spot for that range. The people watching on their phones will miss out on that.

NABA: Does HDR have any special implications for VFX work? Or is it just a question of delivering shots in the correct color space?

PM: It’s a question of delivering shots in that space — and checking it. We hire our colorist, Eric Weidt, for the run of the show. He does retouch work and some effects work on the side when he’s free, but it gives us this awesome opportunity. Literally any time during a working day when we want to check something, he’s right there. We just need to feed him the file and we can go in and look at it. Our in-house compositor, Christopher, takes advantage of that quite often. On a project with David, that level of scrutiny is really helpful because he’s going to scrutinize it 10 times harder than that.

NABA: Did COVID-19 and the ensuing lockdown impact the production?

PM: We had the wind at our backs, because we finished shooting right before the end of February and the WHO declared a pandemic on March 11. That’s how close we cut it. We had many remote features in our workflow already, partly because of working on Mindhunter. David literally moved to Pittsburgh for both seasons of Mindhunter. He was hands-on in a big way, but the editor and our entire team were here in L.A. We would upload to PIX every day, many times a day, and get pages and pages of notes every night. So that flow was already in place. It took us about three days to move everybody to their homes and put systems in their homes, and then we got up and running. I would say the real pain point is that when we’re finishing the final effects, especially the final grading, we do like to be in the same room, and we couldn’t do that this time. But we survived. For grading, we put David in the grading suite by himself. He watched the movie twice on two different monitors, one a really professional model and one a consumer monitor, and we gave him a laser pointer and videotaped his notes.

NABA: So you feel like you didn’t miss a step on that?

PM: I’m not complaining. We didn’t have to modify our schedule. The mix at Skywalker Ranch was similar. We could only have four people on the stage, and three of them were mixers. So that means only David was on the stage, in addition to the mixers.

NABA: Do you use anything special in terms of production tracking software in addition to FileMaker?

PM: I don’t, but I do use FileMaker. We had some success on Mindhunter where FileMaker was tied into the edit system so I could get updates from editorial and modify my estimates based on a current cut. That’s still buggy right now, but that’s probably the most sophisticated thing happening in those terms. I have the benefit of being on in pre-production so I can set stuff up early on as opposed to having to come in after the movie’s been shot and start from scratch.

NABA: What do you use for review and approval?

PM: All the early submissions happen on PIX. As we get close to final, we’ll ask them to send in EXRs. Pre-COVID, we would look at them on a 4K monitor or sometimes even take them into the DI suite. David has this incredible eye. It’s astonishing how he can look at something on his on his iPhone on PIX and give me really sophisticated notes. It’s the same with grading. He knows how to deconstruct an image. It’s uncanny. It’s a real education to sit in a DI with him because he will point something out and explain why something is happening to the image, some artifact or whatever.

NABA: On every film, you’re probably still surprised by things that he comes up with you might not have noticed or thought of.

PM: Yes. In this movie’s case, it was the whole black-and-white of it. That was huge. Many, many hours of discussion and DI and camera testing went into that.

NABA: Into making the decision to shoot black-and-white or figuring out how to capture the best black and white image?

PM: How to capture it, but also what to do with it to make it feel a little bit late-1930s dupey.

NABA: Right. Like some of the — not really halos but shadows around the high contrast edges?

PM: That’s exactly right. Blooming. We refer to it as “blooming in the blacks.” Because of the whole black-and-white look, the DI overlapped into VFX and camera in a bigger way. We were going for something very specific. We spent a lot of time testing. And that’s one thing that I think anybody who does what we do would love to be able to do: test something at any time. We love our tests.

NABA: Were there any scenes where, either in the script process or on the day of the shoot, you had to say, we really need to do this a different way to save time or money in post? Is there ever a trade-off where something really is just too expensive, or do you just make it affordable through ingenuity?

PM: All of those things. We generally manage to make it happen. If there’s a real problem, David and I will have a discussion about how to get there. Ironically, I can’t think of a shot where we had to change something because it was too difficult. I can think of one shot where an effect went away, and it’s that car accident scene where the note flies out of the car. I had that on my VFX list, that there was going to be a CG shot of the note flying out of the car. And then David kept shooting it on the day and, on the best take, the note literally flew out and covered the lens. So what you see in the movie is completely live. I had managed to set aside a little bit of money to get the job done, but I crossed it off the list.

NABA: Are there any other shots in the film that you think would be of special interest to other VFX producers or VFX artists, either because they might actually be invisible even to VFX pros, or because of something unusual about your approach?

PM: A couple of things are going on in David’s mind when he’s on the set. There’s obviously the creative part. But the other part is how to get the most time he can have on set with the actors. That means efficiency is at a premium. He’ll say, “OK, what are the factors here that could slow me down, even just three minutes?” A big example is in the Louis B. Mayer party scene and the drunken dinner party scene at the end, where the flames in the fireplaces are all post. David did not want to deal with any issues, or with the noise of having a real flame there, so he just took that out of the equation. And there are about 100 flame shots in the movie.

That’s one of the things digital has done. Clearly before 2000, when we were mostly film based, it would be hugely expensive to do that on film, even if we were doing it digitally and had to scan the film. To do 100 flame shots? There would have been a big, big discussion about whether that’s the best way to spend money. But we did those with Ollin VFX. They knew roughly how many shots they were getting, set up a pipeline, cranked them through and did a great job. There’s something like that in all David’s projects, where he looks at it and says, “I’m going to do this in post. I just don’t want it to slow me down and steal from my work as a director.”