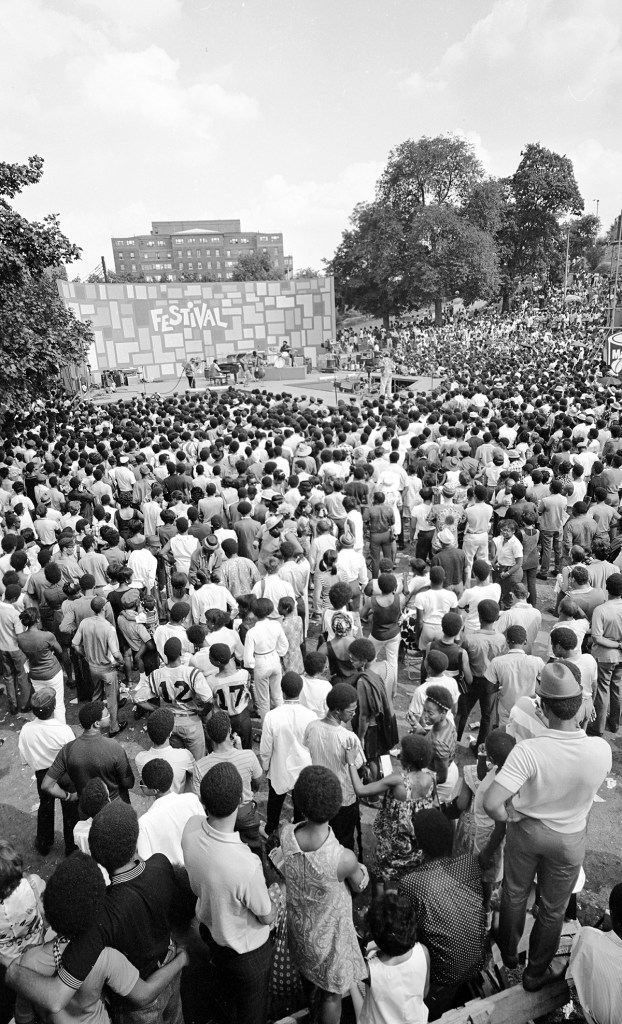

Forget about “hot vaxx summer,” and get ready for the Summer of Soul. Now streaming on Hulu, and in theaters in a limited release from Searchlight Pictures, Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) is the documentary you never knew you needed. Assembled from more than 40 hours of recently unearthed footage shot over the course of six weekend events in New York City, Summer of Soul chronicles the forgotten history of the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival held in what is now known as Marcus Garvey Park.

The New Yorker’s film critic, Anthony Lane, notes that “halfway through a heavy year, the best movie so far — the one most likely to ease the load and lift you up — is Summer of Soul.”

The film offers “not a state of bliss,” Lane writes, “but a precious, precarious interlude of release and relief, before the pressures of an unequal society kicked back in. History chose to commemorate Woodstock, which unfolded a hundred miles or so away, in the heat of the same summer. But history, as so often, went to the wrong gig.”

READ MORE: Questlove’s “Summer of Soul” Pulses with Long-Silenced Beats (The New Yorker)

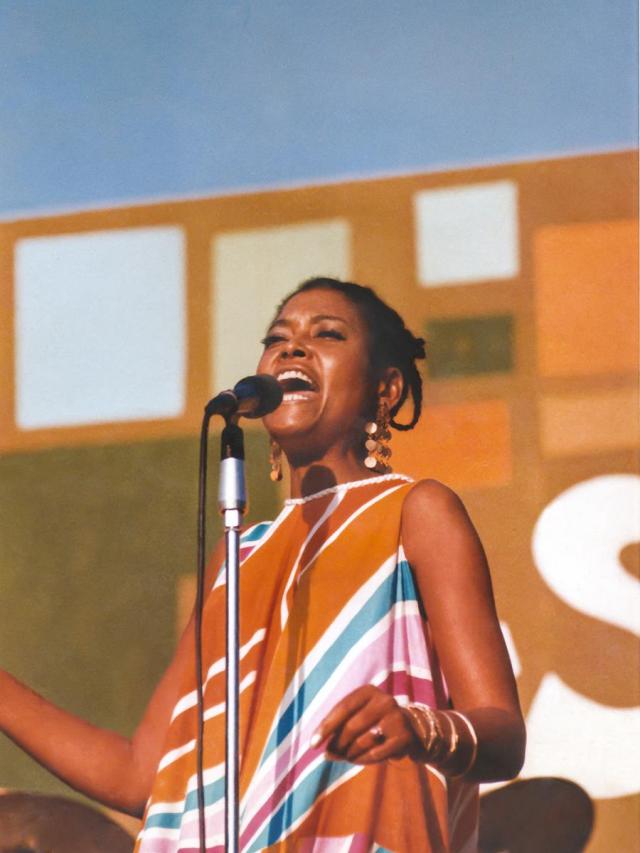

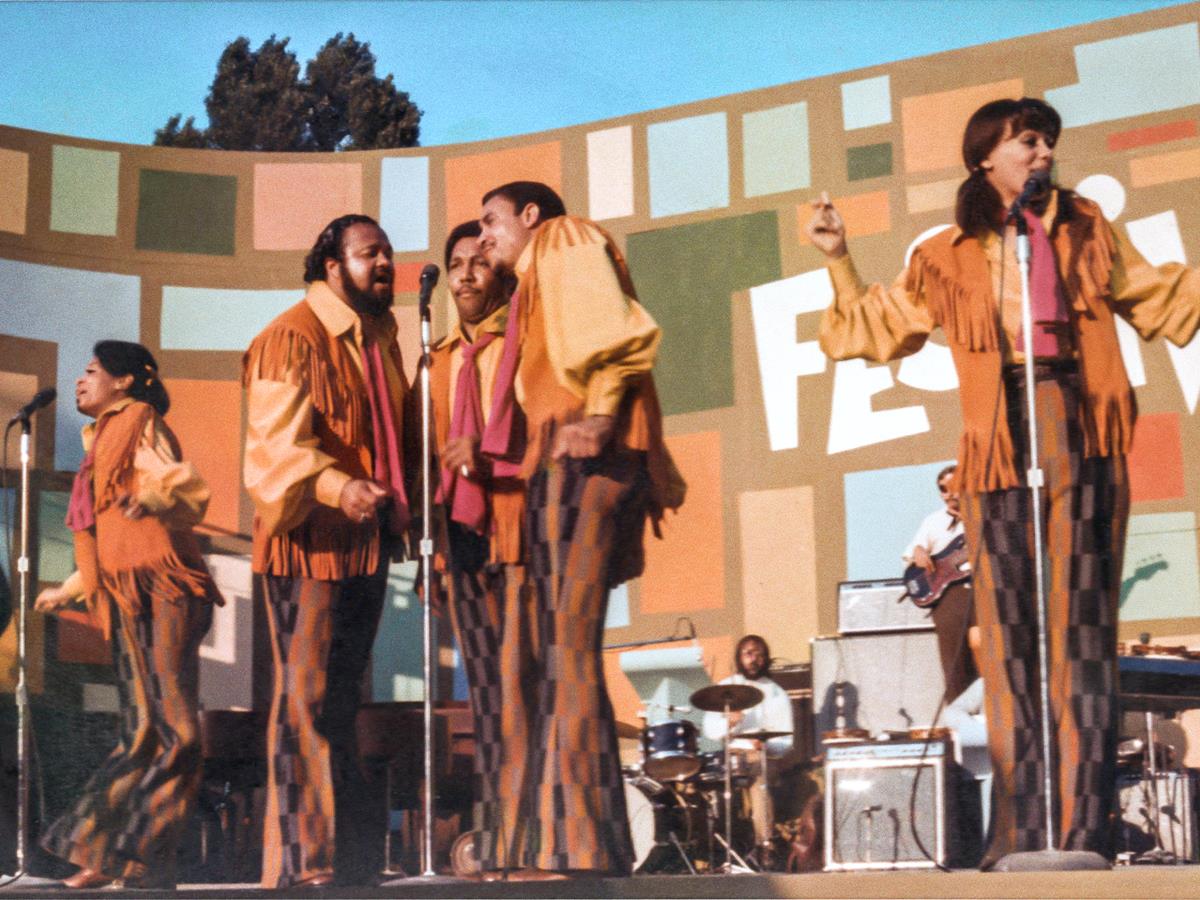

The project, which won both the US Grand Jury Prize and the Audience Award in the US Documentary category at this year’s Sundance Festival, is the acclaimed filmmaking debut from musician and music historian Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson. It includes never-before-seen concert performances by Stevie Wonder, Nina Simone, Sly & the Family Stone, Gladys Knight & the Pips, Mahalia Jackson, B.B. King, The 5th Dimension, and more. By way of intimate, newly restored footage, and recent interviews with attendees and the artists who performed, Summer of Soul documents the moment when the old school of the Civil Rights movement and the new school of the Black Power movement shared the same stage, highlighted by an array of genres including soul, R&B, gospel, blues, jazz, and Latin.

“Sometimes these archival-footage documentaries don’t know what they’ve got,” Wesley Morris opines in his review for The New York Times. “The footage has been found, but the movie’s been lost. Too much cutting away from the good stuff, too much talking over images that can speak just fine for themselves, never knowing — in concert films — how to use a crowd. The haphazard discovery blots out all the delight. Not here. Here, the discovery becomes the delight. Nothing feels haphazard.”

Summer of Soul contains many remarkable performances, but it’s the film’s juxtaposition of concert footage with archival news footage, layered with audio interviews from performers and attendees, that makes it more than the sum of its parts.

“On one hand, this is just cinema,” Morris writes. “On the other, there’s something about the way that the editing keeps time with the music, the way the talking is enhancing what’s onstage rather than upstaging it. In many of these passages, facts, gyration, jive and comedy are cut across one another yet in equilibrium. So, yeah: cinema, obviously. But also something that feels rarer: syncopation.”

READ MORE: ‘Summer of Soul’ Review: In 1969 Harlem, a Music Festival Stuns (The New York Times)

The decision to intersperse the concert footage with present-day interviews with the artists and attendees didn’t come to Thompson until late in the process, he told Todd Jorgenson in an interview for D Magazine.

One of the most touching interview subjects is cultural entrepreneur Musa Jackson, whose earliest childhood memories were of attending the festival at the age of five. “The emotional component of the film was something I wasn’t prepared for,” said Thompson. “Once we showed him the footage, the tears started welling. He didn’t know if he remembered it or if anyone believed him.”

READ MORE: Why It Took 50 Years for the Harlem Cultural Festival to Get Its Cinematic Due (D Magazine)

Summer of Soul was edited by Joshua L. Pearson, the award-winning editor known for his work on the Academy Award-nominated What Happened, Miss Simone?, as well as Under African Skies: Paul Simon’s Graceland Journey, “Keith Richards: Under The Influence, and Whitey: The United States of America v. James J. Bulger.

“Of course it’s a shame that this footage sat in a box in a basement for 50 years, but after percolating all this time, it’s like finding treasure now,” Pearson commented in an interview with Hugh Hart for the Motion Picture Association’s The Credits.

“Last summer was so horrendous, with George Floyd and the pandemic, somewhat parallel to 1968, which was an especially hard year for Black people with the killing of Martin Luther King,” he continued. “So 1969 was a summer of venting and release and I think this summer is going to be like that too. You feel good after you watch our movie.”

While sometimes referred to as “Black Woodstock,” the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival as it would be depicted in Summer of Soul was never going to be the immersive experience provided by the 1970 Woodstock documentary directed by Michael Wadleigh. “The Woodstock film is very immersive because they had 15 famous cameramen wandering around with sixteen-millimeter cameras getting all this great footage making you feel like you were right there in the crowd,” Pearson explained to Hart.

Television veteran Hal Tulchin was brought on to shoot all six concerts at the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival, signing a sponsorship deal with Maxwell House Coffee to finance the production. But there wasn’t enough money for film stock, and the production “only had four cameras on stage, with just one of them pointing out at the audience,” Pearson recounted, adding:

“Since we couldn’t do the immersive thing, Summer of Soul is more about the audience having the privilege of looking at this incredible artifact. The musicians’ sets were really well shot so you experience the excitement of their performances but at the same, it’s like you’re in a museum looking at a beautiful painting or piece of bronze jewelry from [ancient] Greece. And part of that feeling comes from the way we frame the movie, starting off with tape hiss as Ahmir asks someone who was there: ‘What do you remember about this concert?’ We’re setting it up to feel like ‘Oh my god I’m watching something precious that hasn’t been seen in 50 years.’”

READ MORE: “Summer of Soul” Editor on Piecing Together the Nearly Forgotten Black Woodstock (The Credits)

Tulchin had wanted to call the project “Black Woodstock” and, initially, Thompson planned to use the title for his film as well. “The title was my last move,” Thompson said to Lisa Robinson in an interview for Vanity Fair:

“I knew in my heart it would be a disservice to call it ‘Black Woodstock.’ In Hal’s last minute Hail Mary pass, when he attempted to find somebody to make this film, he figured if he could conceptualize it under the Woodstock thing, people would be interested. But still, nobody was. So this film basically wound up sitting in his basement for 50 years.

“It was a working title, and for a little bit I thought of the irony of Black people had constantly been talking about cultural appropriation, so it would be interesting if the tables turned a little bit and we appropriated something established with white people. But then towards the end, deep into the pandemic, around March 2020, I thought I would do it a major disservice if I didn’t let this film stand alone. The very last thing I did was change the title and I also said I wanted a knowing wink — based on Gil Scott Heron’s lyric — ‘When the revolution couldn’t be televised.’”

READ MORE: Questlove Talks Directing, Insecurity, and the Miraculous Found Footage That Led to His New Documentary, Summer of Soul (Vanity Fair)

“From the funky, opening groove of the film’s first song, Stevie Wonder’s slinky jam on the Isley’s Brothers’ “It’s Your Thing,” it is obvious the new documentary Summer of Soul (…or When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) will be packed with little-seen, landmark live performances,” Eric Deggans observes in his review for NPR:

“But watch a little longer, as Wonder sits behind a drumkit to whip off a crackling drum solo. As he works the kit, clips of news reports and pundits surface talking about the crucial political and social issues facing Black people in 1969. And you realize you’re seeing something more.”

That something more invokes the mood of a community that has come together to celebrate its very existence in the face of violence, systemic discrimination and cultural whitewashing and erasure. “By 1969, the country had already endured the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr,” Deggans points out, going on to note that at one point the film even suggests that one reason city officials backed the festival was to avoid potential rioting on the anniversary of King’s assassination.

READ MORE: ‘Summer Of Soul’ Celebrates A 1969 Black Cultural Festival Eclipsed By Woodstock (NPR)

Thompson was immediately drawn to the footage of Wonder playing the drums when he first saw it, intuitively understanding that it made the perfect opening number, he explained in an interview with Clover Hope for Pitchfork. “When I got to the Stevie Wonder drum solo, I knew that was the gob-smacking cold-open shocker of all shockers,” he said. “People have never seen Stevie Wonder in a sort of percussion context. So I figured that’s my little wink to anyone coming in with folded arms like, OK, what’s the Roots drummer going to do with this film? Of course, he’s going to do a drum solo.”

The moment Wonder takes the stage happened to coincide with the historic Apollo Moon Landing, bringing the country’s sharp cultural divide to the forefront, as Thompson highlights in the film:

“When Stevie comes on stage, that’s when Apollo lands on the moon. When he lightly mentioned it, you hear boos, and that was curious to me. Of course, growing up, I listened to Gil Scott and Curtis Mayfield. I’ve heard snide remarks about the moon landing in soul songs, but I didn’t realize the disdain was that strong. Once we heard boos, it’s like, whoa, let’s investigate. Unbeknownst to us, CBS Evening News’ Walter Cronkite happened to send a man-on-the-street [reporter]. It was done in a snarky way, like, ‘While the world stands by to watch history, they’re in the park…’”

READ MORE: Questlove on Restoring Black Music History and Making One of the Year’s Best Films (Pitchfork)

Producers Robert Fyvolent and David Dinerstein compiled an ideal list of directors for Summer of Soul, with Thompson at the very top, but The Roots co-founder wasn’t sure at first that he was the best person for the job.

“We’d followed Ahmir’s career for the last 25 years, and knew he was an extraordinary storyteller with his finger on the cultural pulse. Not only did he have an encyclopedic knowledge of film, his voice in particular delivers an immersive quality that puts viewers in the moment of this historical event,” Fyvolent comments in the film’s production notes.

“It was crucial to find a director who understood music and its history. Someone who could put the footage and its relevance in context. Ahmir embodied all of those things,” Dinerstein adds.

In an interview with Variety crafts editor Jazz Tangcay, Thompson explained his initial hesitation:

“When it was presented to me, one I didn’t believe it in the beginning. Because my ego wouldn’t even let me fathom that you know the all-knowing music snob Questlove didn’t know about something as mammoth as this festival happening,” he laughs. “And then it went from that to, ‘Wait a minute, why am I chosen one to tell this story?’ This is more than just entertainment; this is history. Why are you trusting a first-time driver behind the wheel?”

Thompson “tried hard” to get out of it, he recalled:

“I was like, ‘You need someone real like an Ava DuVernay or Spike Lee to take this because this is too much important in history for you to rely on a novice. I’m the only person in history that was given a winning lottery ticket, and was like, ‘Give it to them give it to them.’ But [the producers] told me that this was my destiny and I had to accept this mission. It was like Mission Impossible, and I had to deal with it. And I’m very glad I did so.”

READ MORE: How Questlove’s ‘Summer of Soul’ Tracked Down Rare Footage of the Landmark Harlem Cultural Festival (Variety)

In preparation for making Summer of Soul, Thompson had the restored footage transferred to DVD to watch on a loop at home. He described his process for reviewing the footage to Haizlip:

“I basically made that my visual aquarium for those five months. Instead of sitting here with my pad and pen and just watching everything, I wanted it to naturally hit me. So, all the TVs in my house, in my office at NBC, my laptop — it was like a screensaver. The concert just constantly played for 24 hours. I kept notepads next to each monitor in my house.”

Once Thompson determined that Stevie Wonder’s performance would open the film, many of the other elements began falling into place. “This is also how I plan shows,” he said. “I feel as though most people remember the first ten minutes and the last ten minutes of any show, but it’s almost like, what’s in between doesn’t matter. Yes, in this case it does matter, but for me, it was like, when people first see this, what do they see and what do you leave them with?

NOT WHODUNNIT, BUT HOW-DUNNIT — DIGGING INTO DOCUMENTARIES:

Documentary filmmakers are unleashing cutting-edge technologies such as artificial intelligence and virtual reality to bring their projects to life. Gain insights into the making of these groundbreaking projects with these articles extracted from the NAB Amplify archives:

- Crossing the Line: How the “Roadrunner” Documentary Created an Ethics Firestorm

- I’ll Be Your Mirror: Reflection and Refraction in “The Velvet Underground”

- “Navalny:” When Your Documentary Ends Up As a Spy Thriller

- Under the Volcano(es): How Sara Dosa Found a “Fire of Love”

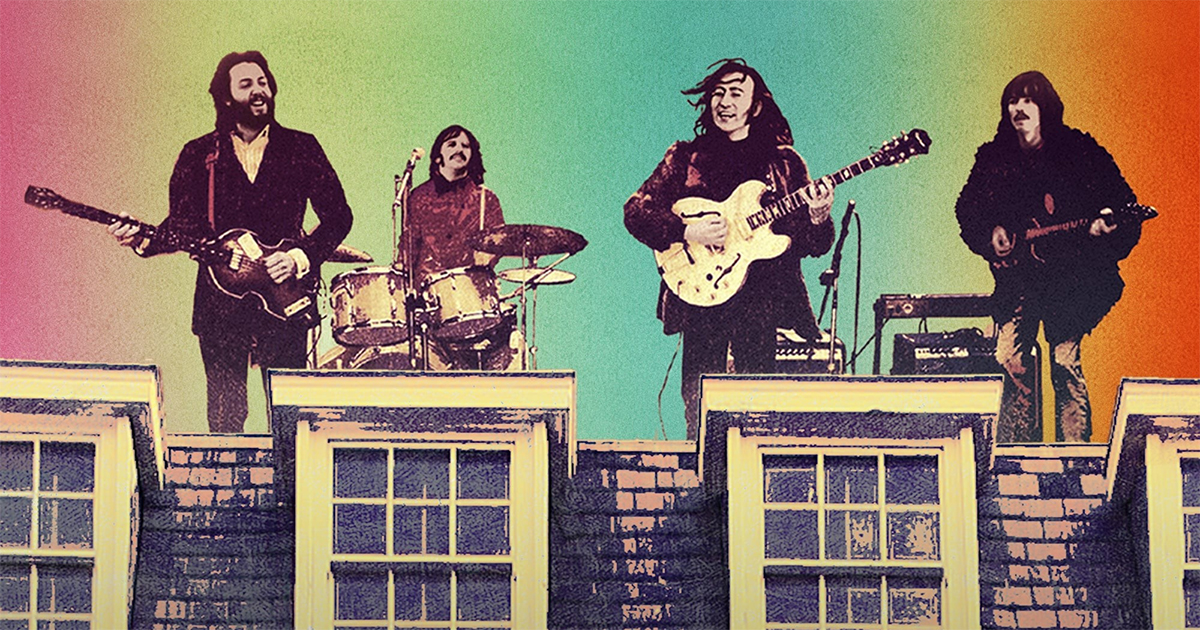

- It WAS a Long and Winding Road: Producing Peter Jackson’s Epic Documentary “The Beatles: Get Back”

The centerpiece of Summer of Soul is the incredibly moving footage of Mahalia Jackson and Mavis Staples as they perform “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” an often-requested favorite of King’s, who had been assassinated just one year earlier.

“I don’t remember how long this performance lasts,” Morris writes in his New York Times review. “It doesn’t really even have an ending, per se. It just simply concludes, with each woman heading back to Reverend Jackson, into the band. But when it’s over you don’t know what to do — well, besides never forget it. It’s an extraordinary event not just of musical history. It’s a mind-blowing moment of American history. And for five decades, the footage of it apparently just sat in a basement, waiting for someone like Thompson to give it its due.”

Thompson initially envisioned this soulful gospel performance for the film’s ending, he told Melissa Haizlip in an interview for Documentary Magazine. “I gave permission for [producer] Joseph [Patel] and everyone to really speak their voice and let me know if I was trailing off into amateur-hour territory,” he said. “For the ending — initially I thought well, obviously, Mahalia [Jackson] and Mavis Staples have to close this; that’s the most magical moment of the thing. And then Joseph challenged me.”

The filmmakers ultimately decided to use Nina Simon’s performance for the ending of the film, Thompson told Haizlip:

“I felt it was more dangerous and edgy, and it spoke more of today to let Nina Simone have the last word, especially with ‘Are You Ready, Black People?,’ with her challenging people to immerse themselves. We live in a time where a lot of performative activism is trying to masquerade itself as actual activism, especially with social media. Once we shifted Mavis and Mahalia to the middle, it elevated the film even more, then of course, Nina’s fiery performance was the hardest to break up because that entire 45 minutes was the most magical. I’ve never seen a person just so sure of themselves in new territory. She’s not singing jazzy love ballads like ‘My Baby Just Cares for Me.’ She’s going into a new territory of activism. So, once you have those three, the story writes itself. And this is a story of change.”

While the original footage did undergo a restoration process, it was important to Thompson that the visual and sonic artifacts of the era be retained, he said to Haizlip:

“Visually and sonically I wanted it to be as true to 1969 as we could get it. The one thing that I would love to really take credit for was the sonic miracle that was the mix. Hal Tulchin’s widow let us go through his basement archives, where a lot of our questions were answered because he kept all the paperwork, he kept the backline, he kept what was rented, he kept the blueprint of building the stage to the soundboard. I was amazed that it was only 12 microphones; when you watch the movie the way that I did, you have to watch with a different set of ears and eyes.”

The mixes and the reels were handed off to one of Thompson’s favorite music engineers, Jimmy Douglass. “He started with Barry White when he was 17 years old and he’s gone through a whole ring,” Thompson recalled. “I got familiar with him once Timbaland made him his engineer.”

Widely known as “The Senator,” Douglass also served as music mixer on the 2018 Aretha Franklin biopic, Amazing Grace.

“He really gave us a great mix,” Thompson continued. “We did a 5.1 and we did a Dolby version. The way that B.B. King’s performance comes off in the movie theater; it’s literally like you’re sitting on stage listening to how clear and crisp it is with very minimum amplification. It’s so weird that that’s the one thing that I’m taking away from this movie that I might apply to my real life.”

READ MORE: ‘Summer of Soul’: A Conversation with Questlove about Black Joy (Documentary Magazine)

Restoring the footage was a delicate process, Thompson told The Hollywood Reporter’s Rebecca Keegan:

“It took about four months to clean, to make sure it didn’t crumble inside of modern machines — 47 reels. There wasn’t a budget for lights. They only had one sponsor, and that was Maxwell House. So they had to make sure that the stage faced west so that they could take advantage of the sun. It was recorded with barely 60 microphones for full-blown orchestras. We had one sound-glitch problem: Freddie Stone’s guitar amp. What you’re listening to is very close to what it was in 1969.”

The COVID pandemic arrived just as Thompson and his team completed all the arrangements for filming interviews, he told Keegan. “The first week of March, we had this elaborate lineup set. From around March 13 till mid-April, I was just sulking and under the sheets, thinking ‘this movie’s going to go to hell,’” he said.

But the pandemic lockdown actually helped Thompson rethink his approach to the film. “It’s so weird, this film actually became better,” he said to Keegan:

“It started out as, ‘OK, let me just curate the best performances I can.’ Suddenly, COVID forced me to also tell the story of the concert. Mainly because the story was happening again in real time. The circumstances that caused the concert to happen back in 1969 were starting to happen in 2020. One thing I always wanted to uncover is, a lot of people are often amused at how we catch the spirit, so to speak, in terms of our excitement in music, like when you see James Brown screaming or you see Jimi Hendrix do a mammoth guitar solo. As I was watching this, I realized that there was something deeper under the surface. I was like, ‘OK, we’ve got to start finding people [who were in the audience].’”

READ MORE: ‘Summer of Soul’: Questlove on His Documentary Homage to “Black Woodstock” (The Hollywood Reporter)

Making Summer of Soul was Thompson’s “chance to correct history,” he said in an interview with Brandon Pope for Ebony. “It’s a story that, for so long, hasn’t been shared.”

Tulchin filmed a once-in-a-generation party in preparation for a concert film that never happened, and the footage went largely unseen until it was put in storage. Fifty years later, the unprecedented footage was finally unearthed.

“I myself didn’t even know the story,” Thompson admitted to Pope. “If I were a betting man, I would have bet all my publishing that this never happened.”

It was about three months before Thompson said “let’s make a movie,” and began to assemble a team to help him craft the narrative. “I just told my production team to be really transparent. Do not let me walk out in the world with a wine stain on my suit without telling me.” said Thompson. “Credit to my producer, my editors and everyone involved in the process of helping me make it this because I wanted to make an effective educational piece.”

READ MORE: The Revolution Was Not Televised: Questlove’s ‘Summer Of Soul’ Unearths the Black Woodstock That Was Kept Hidden (Ebony)

The cultural significance of Summer of Soul was immediately apparent to Thompson, he told Jonathan Bernstein in an interview for Rolling Stone.

“This was supposed to come out 50 years ago, and I was supposed to see this movie as a four-year-old,” he stressed. “When Woodstock came out, the movie made household names out of every artist who appeared in the film. The legend of that concert wound up subsequently defining a generation…. And so, as a result, when you think of the late Sixties, you think of hippies, mud, free love, Hendrix, all of those things. This could’ve been such an adrenaline boost to black music culture, and it wasn’t allowed.”

As an example of what could have been, Thompson points to Prince’s memoir, “The Beautiful Ones,” which contains a detailed recollection of seeing Woodstock in theaters with his father in 1970. The experience proved to be a formative one for the artist, and Thompson wondered if Summer of Soul could have had a similar effect on Prince and other artists.

“His dad could have took him to see this film,” he said to Bernstein. “Who knows what could have happened?”

READ MORE: A Festival Dream Deferred No More: Inside Questlove’s ‘Summer of Soul’ (Rolling Stone)

Thompson premiered Summer of Soul in late spring at Marcus Garvey Park, the same location where the Harlem Cultural Festival was held in 1969. The date was Saturday, June 19 — Juneteenth, the new federal holiday commemorating the emancipation of African-American slaves. During the screening, the musician-turned-filmmaker found himself surprised by some of the elements that grabbed the audience’s attention. “They were responding to stuff that I hadn’t considered,” he told Farrell Evans in an interview for The Undefeated. “Usually you show the film first with test audiences, but we decided to screen it here in Harlem.”

READ MORE: The Harlem Cultural Festival footage is getting wider recognition in the new ‘Summer of Soul’ documentary (The Undefeated)

Editor Joshua L. Pearson was also at the event, he recounted in an interview with The Credits. “It was kind of mind-blowing,” he told Hugh Hart, adding:

“Everyone clapped and cheered after every song. During the gospel section, people around me were testifying, holding their hands up in the air. And it was weird because they’d built this backdrop for the stage behind the screen that was just like the original backdrop made of multicolored blocks that you see in the film. I felt like I’d fallen into some kind of wormhole, with the live event from 1969 being transmitted through time in the same spot. Trippy is the only word I can think of to describe it.”

READ MORE: “Summer of Soul” Editor on Piecing Together the Nearly Forgotten Black Woodstock (The Credits)

Want more? Listen to Thompson discuss Summer of Soul in an interview with Audie Cornish for NPR in the audio player below:

You can also watch Thompson in an interview with CBS Sunday Morning contributor Hua Hsu: