In the movies, the before and afters of an apocalypse usually has the post-event world looking desaturated, burnt out, drained of color. Not so Station Eleven, which flips that convention on its head.

In the 10-episode series that just finished on HBO Max, the apocalypse results from a flu that has no incubation period and causes near-immediate death.

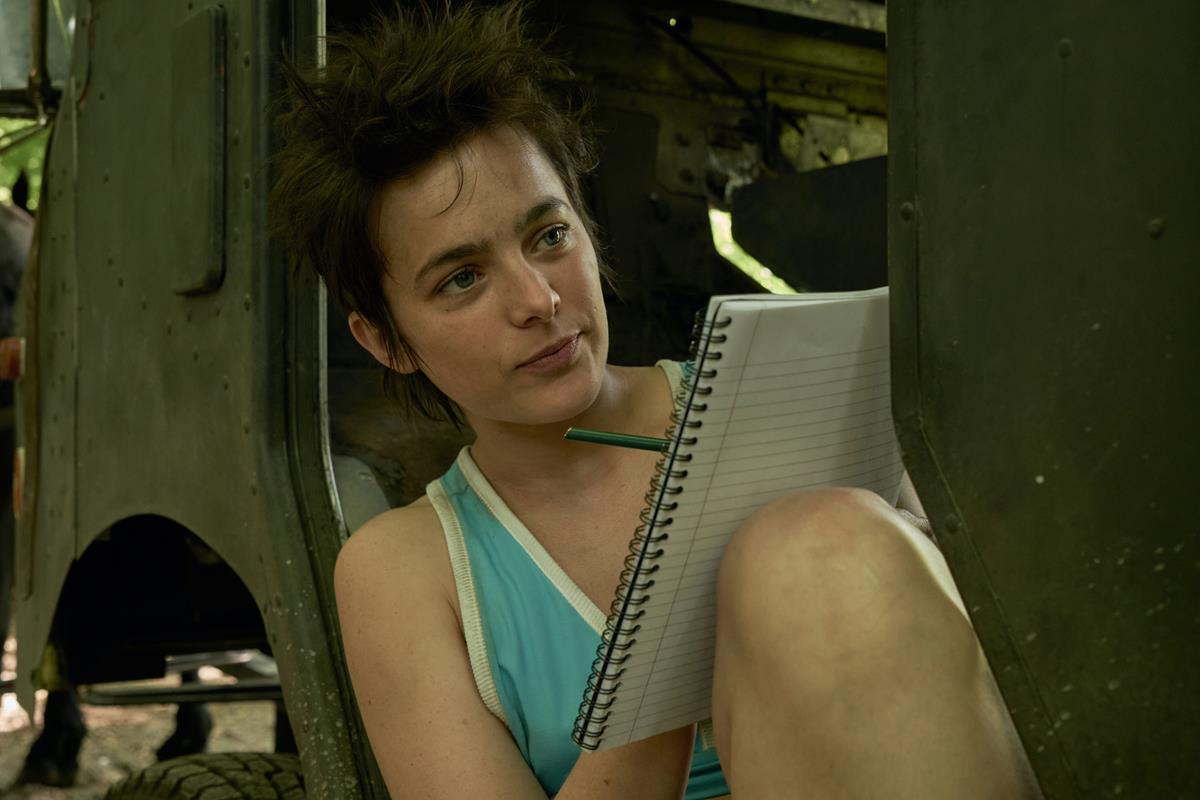

In adapting Emily St. John Mandel’s 2014 novel, writer and showrunner Patrick Somerville (The Leftovers) traced three story worlds: a traveling Shakespearean troupe, a cult of kids led by the prophet Tyler (Daniel Zovatto), and a group of survivors living in an airport.

The series alternates between past and present timelines to show the pivotal hours leading up to the crisis, the immediate aftermath, and those who have adapted to the new circumstances of their world 20 years later.

This could be a set up for a “puzzle-box” of elements that fire up fan communities in shows like I, Robot, Westworld and Yellowjackets, but Station Eleven sidesteps this.

“It isn’t that the post-apocalyptic drama doesn’t supply answers — it does, in increasingly rewarding layers as it unfolds — but rather that the questions that really matter can’t be addressed through plot mechanics,” Lili Loofbourow suggests in her review for Slate.

“We are not interested in how the pandemic started, or who engineered it, or even how exactly it works. We don’t even especially need to know the particulars of the ‘Station Eleven’ graphic novel within the show. What matters far more is the feeling the book creates and what that feeling does.”

That feeling is evoked most strongly in an aesthetic that acts an antidote to the dour color palette and mood of other post-apocalyptic motion picture narratives on television and in film.

“Laced with humor and heartache, it’s perhaps the brightest, most fanciful end-of-the-world drama you’ll ever see,” says Joshua Meyer at Slashfilm.

While Nicole Clark at Polygon insists that the “Beautiful, lush cinematography gives scenes a sense of contemporaneousness — resisting the dour tones that often mark the apocalypse genre.”

The visual (production design + cinematographic) concept was have the present feel like the future, and the future to feel like the past.

READ MORE: Station Eleven found a silver lining in the post-apocalypse (Polygon)

“In many ways, we were trying to invert the post-apocalyptic genre,” Somerville tells Emily VanDerWerff at Vox.

“Hiro Murai [who directs the pilot] always said he wanted to be there when we were talking about year 20 [after the plague that kills most of humanity]. Quiet, big, expansive, beautiful, green. Not destroyed. Just still.”

In postproduction the filmmakers actually deemphasized color in scenes set before the apocalypse.

“Year 20 is very naturally lit with lots of bright sunlight and lots of colorful greens and flora and lots of saturation,” explains DP Christian Sprenger, who set the series look with Murai in the pilot.

“We wanted that world to feel welcoming, and we wanted to push against that concept of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road’s very gross, dirty, almost monochromatic future, that sad apocalypse aesthetic. Where that led us was that year zero, the world we’re currently living in, wanted to feel a little bit more subdued and slightly desaturated.”

He also told VanDerWerff that they deliberately chose locations with artificial lighting: subway stations, a theater, even the streets at night. “Everything has this stark, manmade aesthetic. We intended to let that be what the sci-fi future aesthetic normally feels like. And when you jump forward to the future, that almost feels like 200 years ago.”

Sprenger told Robert Lloyd at the Los Angeles Times that the inspiration for shooting with an ARRI Alexa Mini large format camera was to help tell a story “about a few seemingly insignificant people up against these giant man-made and eventually natural landscapes. This idea led us down the path of putting our small little characters against these large-scale wide frames — feeling the contrast of scale to significance.”

READ MORE: Meet the cinematographer whose ‘controlled naturalism’ is changing the face of TV (Los Angeles Times)

The DP’s work on the premiere episode, “Wheel of Fire,” was nominated for the 2022 Emmy Award for Outstanding Cinematography for a Limited or Anthology Series or Movie.

Sprenger discussed his use of the ARRI Mini LF and MasterBuilt lenses in an interview with IndieWire’s Erik Adams and Chris O’Falt:

“At its core, the story of Station Eleven deals with the common man’s relationship to the structures that modern society has built. In the first episode, our character and audience are constantly encountering incredible scale in the architectural wonders of the city of Chicago. Pairing these unique modern optics with a large format sensor allowed the camera to embody that sense of scale and afforded greater control over sharing it with the audience.”

READ MORE: Emmys 2022: Cinematography Nominees on How They Shot the Year’s Best Shows (IndieWire)

Station Eleven is not the only show to imagine the post-apocalypse in a vivid color palette. Mad Max: Fury Road, for instance, is full of crisp blues and burnt yellows, highlighting its desert setting. I Am Legend and The Walking Dead have been set in worlds where greenery has overtaken what once were human spaces.

“What sets Station Eleven apart is its willingness to push those vibrant colors to an extreme,” VanDerWerff writes at Vox. “Every time the series drops us into a world where humanity is rebuilding, despite the devastation of the Georgia Flu, that world feels almost inviting.”

READ MORE: In Station Eleven, the end of the world is a vibrant, lush green (Vox)

Costume designer Helen Huang picks up the theme: “A large part of this project is about optimism and memory,” she says. “Those two things also spark color, because if you look at our world as it is now, if you took away all the people in it, it’s full of color. It’s full of graphics. It’s a memory of our civilization. It creates this world that’s separate from all the other language of the post-apocalyptic world that’s out there.”

Steve Cosens, who shot four episodes, told Slash Film that his direction from Somerville was to depict a future that wasn’t daunting.

“Even though we’re in this kind of post-apocalyptic, post-pandemic world, he wanted nature to feel that it’s friendly. It’s not like some of these other post-pandemic or post-apocalyptic shows where nature is all burnt out and kind of scary. There would still be some lyricism in the design of the sets or there would be pops of color.”

READ MORE: Station Eleven Cinematographer On Capturing The Post-Apocalyptic World Of The HBO Max Series (Slash Film)

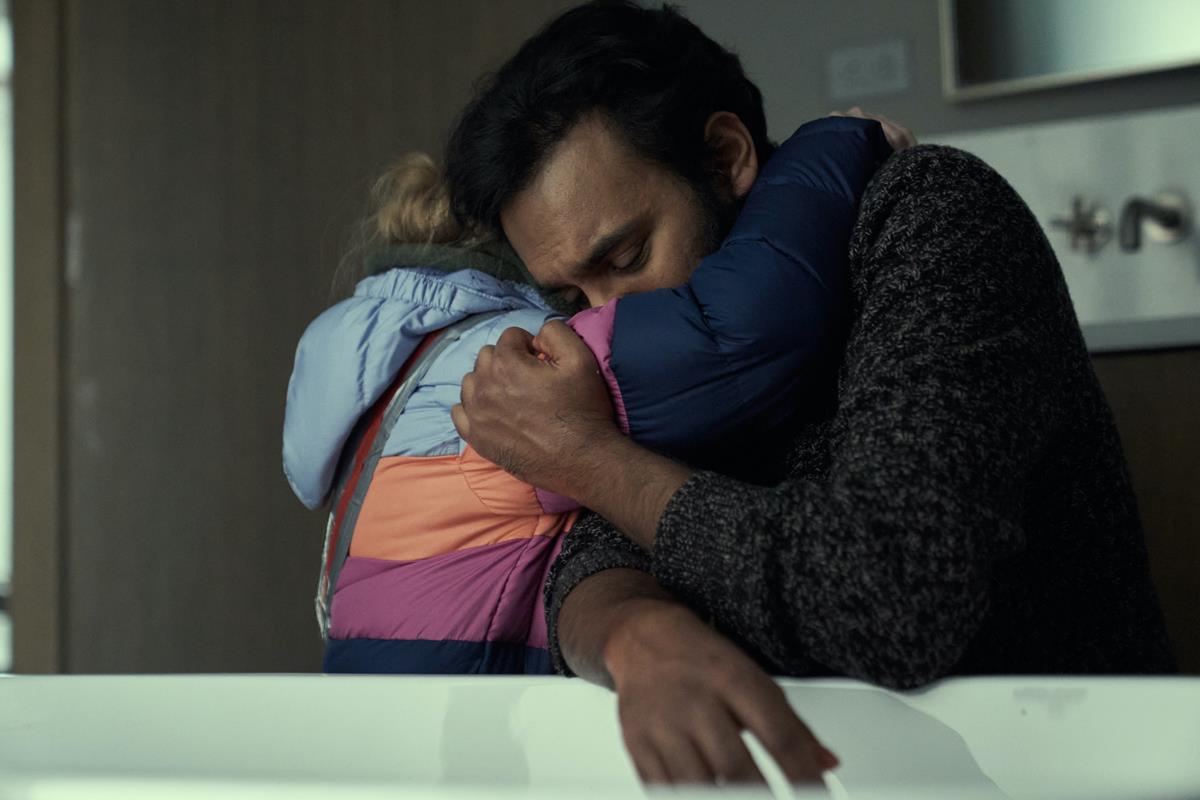

The color approach aside, there’s another ray of hope that Station Eleven radiates — that of basic human connection. Instead of going all Lord of the Flies or selfish rogue as elements of humanity are often portrayed in the aftermath of zombie-geddons like 28 Days Later or A Quiet Place II, Station Eleven eases those psychic blows by saturating its plotlines with “excessive, frankly rococo” connections, writes Loofbourow in Slate.

“The show isn’t following some supernatural principle according to which everyone in its universe is connected. Rather, it makes it seem that the reason we’re hearing this particular set of stories is because they are connected. Station Eleven is obviously and unsubtly interested in art — art as artifice, art as authenticity, and art as a preserver of civilization that stands in opposition to civilization’s less savory aspects.”

READ MORE: What Made Station Eleven So Rewarding (Slate)

Want more? Director and producer Hiro Murai and producer Nate Matteson sit down with Gold Derby’s Rob Licuria for a discussion about building a post-apocalyptic narrative that is “about rebirth, not despair”: