The standout musical number of Into The Heights almost didn’t make the cut. A sequence in which the Latino community’s matriarch Abuela reminisces about her childhood in Cuba and the events that have led her to Manhattan was nearly culled until the filmmakers worked out a way of including its emotional punch.

“That number — “Paciencia y Fe” — was scripted to go much earlier in the movie but in early screenings we debated cutting it out altogether because we weren’t sure how best it would service the story,” says Myron Kerstein, ACE, the film’s editor. “That would have been tragic since it might arguably be one of the best musical numbers ever put on screen.”

The number was originally designed to be played out against a simple black background but evolved to be shot on board a 1940s style subway car as a metaphor for Abuela’s journey as a young immigrant to New York. They shot studio interiors of the car with location shots in a disused metro station, now just used for maintenance and garbage, underneath 81st Street in the Bronx.

In the end, Kerstein suggested to director Jon Chu that they move the number into a later sequence, shuffling a couple of others around from the order of the original stage version, and effectively bringing the first act to a close.

“It was just an idea, but once the producers agreed it was a question of how do we make it feel organic. Can we have a big set piece in the middle of which is someone passing away?”

Joining Forces with Jon Chu

In The Heights is, of course, the big screen adaptation of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s colorful evocation of life, love and dreams in Washington Heights. It won multiple Tony Awards during Broadway runs from 2007 and launched Miranda’s career. He exec produces (cameos, too) from a script by Quiara Alegría Hudes and selected Jon Chu to direct on the strength of other dance films (including Step Up 2: The Streets (2008), Jem and the Holograms (2015) and a pair of live concert films featuring Justin Bieber) and, more pertinently, the cross-over hit Crazy Rich Asians.

Kerstein cut that show for Chu and since then the pair have made two pilots (Good Trouble for Disney and AppleTV+ drama mystery Home Before Dark) “developing a shorthand and building trust.”

“I could have cut it a million ways. I probably did cut it a million ways. But there was only one right version of this story that conveys chaos with an element of danger.”

— Myron Kerstein, ACE

Kerstein didn’t have that relationship with Miranda. “Jon and I wanted to convey to Lin-Manuel that his baby was in good hands. I had to prove that over the course of the post process.”

When Kerstein joined Chu on Crazy Rich Asians he knew the director was already attached to direct. “Every filmmaker wants to work on a musical and I thought maybe there might be a chance for me to work on his next film. When he did, and I read the script I had no idea of the emotional content of the story until I arrived in New York and watched some rehearsal footage intercut with storyboards.”

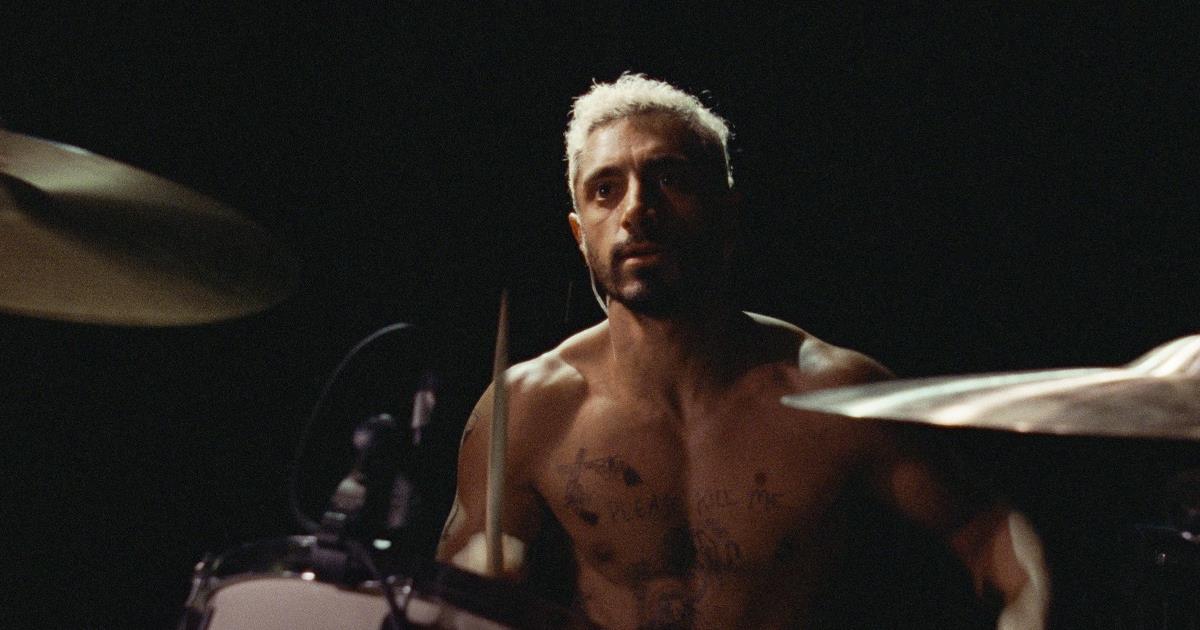

Anthony Ramos as Usnavi and Melissa Barrera as Vanessa in Warner Bros. Pictures’ “In the Heights,” a Warner Bros. Pictures release.

Principal Photography

It would have been easy to shoot the whole film on a Warner Bros sound stage but Miranda and Chu decided to shoot for a month on location in the Heights itself, eventually replicating an entire intersection on the lot. Alice Brooks used a Red camera in a Panavised DXL2 housing with Panavision anamorphics to defocus wider NYC vistas and concentrate on the performances.

“I had gone to early rehearsals of the choreography but my approach was not to get in the way,” Kerstein says. “My credo was don’t let the editing dictate the spectacle of what the dancers were doing. I am just there to support it. Jon and I didn’t want to over cut like a music video to make it more splashy. What was important was making a deep emotional connection with the characters. Everything else was secondary.”

The opening of the film has hero Usnavi talking about beach life in the Dominican Republic. He’s in his bodega in the Heights with dancers reflected in the shot outside the store.

“We had 15 takes to choose of that moment but they were all great. Debating which was the best moment of them sliding down the building and kissing was the hard part.”

— Myron Kerstein, ACE

“I had all the footage to cut to those dancers but we decide to let this moment breathe,” Kerstein says. “The dancers are supporting his story.”

For the number “When the Sun Goes Down,” actors Corey Hawkins and Leslie Grace appear to dance on the side of a tilting building.

“We had 15 takes to choose of that moment but they were all great. Debating which was the best moment of them sliding down the building and kissing was the hard part.”

Finding an Opening

Kerstein, who had previously edited Raising Victor Vargas, Nick and Norah’s Infinite Playlist and numerous episodes of HBO series Girls, brought his “vast cutting experience and knowledge of New York City” to In The Heights, notes Filmmaker Magazine’s Erik Luers, “and the results are as kinetic as they are subtle.”

Building the opening sequence for the film was a puzzle that had to be built very slowly, Kerstein told Luers:

“I literally had images of the George Washington Bridge pulled from Google Maps to represent some of the aerial footage [in the film]. I had stock footage of people going to work and representing the “community chorus.” Jon then wanted to incorporate the beach into the opening sequence and wanted bits of text to appear on screen and to have Usnavi walk over a manhole cover in Washington Heights, spinning it with his foot like a record on a turntable. That opening sequence made us design and, for the viewer, establish, the visual grammar of the entire movie. The opening hints at the magical realism we include later in the film, as well as establishing how they work in relation to the moments that are more grounded. Then we incorporate all of this aerial footage, complete with jump cuts and shots that just hang on Usnavi’s face as he stares out the window (the ensemble dancers appearing via the reflection across his face). There’s an equal sense of scale and intimacy in that opening number and I think it represents what the film is.

“But yes, that took a long time to build out. We would spend our time experimenting, suggesting things like, “OK, we’re going to be playful with this moment. Let’s use the beach/narration device to purposefully pull you out of the movie, so that the viewer will go, ‘Wait, they stopped the story? Will you get back to the story please?’” And having Usnavi tell his story to a group of children on that tropical beach implies that that’s ultimately where he winds up moving to, right? But that wasn’t necessarily meant to trick anybody, as the beach is an essential part of our taking momentary breaks from the film’s musical numbers, of reminding us that Usnavi is telling his story and that it’s important to retell that story to future generations. It was a big puzzle, with numerous discussions, a lot of experimentation, and a lot of failures.”

READ MORE: “My Cutting Process is Very Old School”: Editor Myron Kerstein on In the Heights (Filmmaker Magazine)

Kerstein broke down the production for the film’s opening musical number, “In The Heights,” further in an interview with Variety artisans editor Jazz Tangcay. Rather than shooting over several consecutive days, the sequence was achieved over the course of the entire shoot.

“The opening was about whether we were going to use jump cuts or words on the screen, or stop a scene on a manhole cover, and then spin it back up with a record scratch. We could stop a scene to show Usnavi (Anthony Ramos) and Vanessa (Melissa Barrera) flirt. We wanted to plant our flag to say that this wasn’t going to be a regular Broadway show,” Kerstein recounted.

“I was working on that for six months,” he continued. “It was shot over the course of the shoot. We had to shoot the salon ladies for exteriors and interiors. For example, the inside of the salon was on a set in Brooklyn so that was shot on one day, and due to scheduling, the interior was done another time.”

The starting and stopping, he noted, was Chu’s own idea. “it’s not in the musical,” Kerstein said. “He wanted to be tricky with the audience and tease them that it wasn’t going to be all the way through.”

READ MORE: ‘In the Heights’ Opening Number Took Months to Cut, Says Editor Myron Kerstein (Variety)

Purple Rain and All That Jazz

Filmic references for Myron in prep ranged from classic musicals like The Musical Man and Grease to Purple Rain and even the musical comedy Road films starring Bing Crosby and Bob Hope. Clips from Busby Berkeley type musicals (to which the number “9600” pays homage) or those starring Esther Williams like Ziegfeld Follies were also part of the mood board.

“All those films had an influence to me. Some were very commercial, some have a typical Americana representations. Others like Purple Rain are more grounded.”

All that Jazz was particular influence in its interweaving of story with dream or hallucinatory elements.

“There wasn’t any one film that we followed, rather it was this bombardment of movies constantly swirling in my head,” Kerstein says.

Creating Blackout

Back to “Paciencia y Fe,” which is rolled up in the editor’s biggest dilemma for this movie.

“There wasn’t a clear road map for telling the story of the night where there’s a blackout in the neighborhood,” he explains. “We go from back-to-back musical numbers starting in a dinner scene (“When You’re Home”) which has its own verité experience with a lot of handheld and improv. Then we cut to “The Club” where we need to have this heat and fire and energy and to experience what it feels like to be sucked into this night.

“We’re building into a West Side Story extravaganza (“Blackout”) with gangs of girls and boys dancing, there are fireworks in the sky and these reflect off the buildings, there’s aerial footage, dancers with sparklers, breakdancing and interlapping plot lines.”

He says, “I could have cut it a million ways. I probably did cut it a million ways. But there was only one right version of this story that conveys chaos with an element of danger.”

The movie dives into “Pacencia y Fe” then dovetails with “Alabanza” conveying the mood of the morning after the night before — or rather the mourning for Abuela in which the Heights’ community unites as one.

“This is supposed to be the pay-off emotionally for the excitement and confusion of the evening before,” he says. “The challenge I had was getting from that dinner scene to “Alabanza” because in reality it is one big set piece.

“I told my edit assistant that I wanted ‘Blackout’ to feel like one of those Instagram videos of July 4th when Washington Heights is alive with fireworks. It’s not a war zone but it should be loud, very noisy but then, in order to feel the weight of the moment when the character passes away, I wanted quiet.

“We did cut the film 30 minutes shorter but to me that experience is not the most fulfilling. This film lives and dies by the ensemble of it all its intertwining narratives and character arcs. They are like dominos — remove one and the whole collapses.”

— Myron Kerstein, ACE

“I revisited a moment we did in Crazy Rich Asians where we dropped the sound down really low as a character steps into water at the wedding. There is this hush that I wanted to recreate.

“We then cut to one of my favorite shots in the film which is simply footage of an empty chain linked fence. Then you see one woman walking back home alone with a sparkler. I just wanted to feel the moment of quiet and of a night ending.

“We cut to Usnavi, and here I called on the storytelling of All That Jazz. He is contemplating what just happened. This allows the audience to take in the whole evening that has journeyed emotionally from joy and fun to sorrow.”

The Sound of Music

Although some of the vocals had been pre-recorded, much of the singing for In The Heights was recorded live during filming, which meant that Kerstein had to contend with varying levels of audio while cutting. The editor described his decision process for choosing between live and pre-recorded audio to Steve Hullfish during a recent episode of the “Art of the Cut” podcast.

“Sometimes I mixed and matched, but oftentimes what would happen is that we’d start a song acapella live, or if we went further into the live they’ll have prerecord in an earwig,” he recalled. “But generally, my rule was if they were doing it live, try to use it as much as possible.”

Certain musical numbers, like “When You’re Home” or “Champagne,” were all live, Kerstein shared. “In both of them, that whole one-take Steadicam bungie camera shot is all live. Anytime Usnavi is rapping, like in ‘Carnaval’ or in certain sections throughout the film, there are just tons of little places where we would place it in,” he said.

“I try not to worry too much about the sonic differences, to be honest with you,” Kerstein added:

“It was helpful because I was cutting in 5.1, so I was able to place all the vocal tracks, whether it was prerecorded or live, in the center channel. So, it gave me the feeling that it was all coming from the same place. It kind of fooled me, and sometimes I would EQ it a little bit just in my assembly process, or if it was something live in the club, I’d give it a little reverb, deverbing, or whatever tools I could use in the Avid, but I tried not to get too much in the weeds on that stuff because I knew it was going to get better later.

“I also didn’t know how much live we were going to keep. I think at the beginning of ‘96,000,’ those guys walking down the street, that’s all live except for Benny, for example, because Corey’s voice was a bit rough. He had a cold or something that day, so it’s all live except for him. It was just a mix and match and for the most part it worked really well. It was astonishing how great they all were.”

Cutting in 5.1 Surround Sound provided a theatrical experience inside the edit bay, said Kerstein, but using it meant that he quickly had to learn new tools. “At the end of the day, it’s like your audio mixing tool except you now have dimensions,” he explained to Hullfish:

“Wyatt Smith was in the edit room that I took over right before he left, and he had cut Into the Woods. So, I went up to him and I said, ‘I think I’m going to keep the 5.1 setup you have in your room. Can you teach me?’ He basically sat down with me for an hour and said, ‘This is how you do it.’ Then, I just knew that Jon Chu would really benefit by hearing the theatrical approximation of what it would sound like in the theater in my edit rooms, so I thought, ‘I’m going to go for it,’ and I did it.”

Kerstein also recounted how he worked to avoid a music video aesthetic for the musical numbers. “I was trying to really treat musical numbers like scenes and not recordings of people singing songs,” he said.

“I just tried to keep it grounded, cinematic, and to make it feel like the storytelling doesn’t end just because you’re singing. So, I treated the vocals like dialogue, and any other scene I treated the music like an action sequence in Star Wars. It’s not laser beams shooting, it’s literally a drum beat. That was my beginning philosophy was to try to treat this like a scene, not people singing songs that you’re watching. The difference is so intangible, but that was really my mantra.”

READ MORE: Art of the Cut: Behind the Scenes of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s “In the Heights” (Frame.io)

Tick, Tick… Boom!

Kerstein cut the picture at Company 3 in New York and had the picture locked in February 2020, just before the COVID-19 lockdown. A few months later Warner Bros. decided to delay release by a year. For Chu and Kerstein the extra time was a bonus. The studio agreed to re-open the picture edit and the pair, now in LA, used Evercast sessions to make some final changes.

“We lifted some key scenes and put back a couple. We were able to polish the musical numbers a little more and the music dept had time to finalize the mix. Having that luxury to revisit the film, gain a different perspective and to make changes is rare indeed.”

In The Heights clocks in around 140 minutes but Kerstein says the length is right.

“We did cut the film 30 minutes shorter but to me that experience is not the most fulfilling. This film lives and dies by the ensemble of it all its intertwining narratives and character arcs. They are like dominos — remove one and the whole collapses.”

The editor has segued straight into Tick, Tick… Boom! a musical written by the late composer Jonathan Larson who inspired Miranda’s own work as a lyricist. Miranda is directing for the screen for the first time and the show is released to Netflix later this year.

“I’ve spent all these years dreaming of doing a musical and suddenly I get two incredible shows in a row for arguably the Shakespeare of our time,” Kerstein says. “For a middle class kid from San Diego who finds himself working on these amazing films this is mi Sueño come true.”

Want more? listen to The Hollywood Reporter‘s “Behind the Screen” podcast episode with THR tech reporter Carolyn Giardina featuring In The Heights supervising sound editor and rerecording mixer Lewis Goldstein, production sound mixer Drew Kunin, and editor Myron Kerstein: