There are few events that capture the full attention of a country, let alone the world. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is both a crisis and an opportunity to watch history unfold in nearly real time.

For some of us, this watching the war’s breaking news feels fraught. We want to bear witness, to not look away. We might feel the need to know — without a sense of how this knowledge will change anything, other than our headspace.

War has always been commoditized. But in a U.S. media ecosystem occupied by 24-hour news networks, the coverage of conflict is a ratings opportunity, a chance to regain viewership that dipped significantly in 2021, with flagging interest in national politics and generalized attention fatigue.

Although the timing is clearly coincidental, it is significant that networks have news of this magnitude to cover at a time when both institutional trust and interest in national news were flagging. Bad news for democracy is, sadly, usually good news for the information industry.

And for those in Ukraine, Russia and Eastern Europe, the stakes are obviously far higher. Much of this war is being fought on the airwaves and via social media, with disinformation and propaganda playing an outsize part in the conflict.

How We’re Tuning in

The networks and cable news have mostly gone back to a familiar playbook, trotting out foreign correspondents and stringers to make sure that the latest coverage reflects what’s really happening.

Poynter’s Tom Jones noted early on in the conflict: ‟This is, obviously, a fluid situation that is moving by the minute. The Washington Post has a live feed of the developments, as does The New York Times and CNN.“ Other outlets have since added their own.

‟As Vladimir Putin launched his invasion of Ukraine, triggering what has already been called the most serious conflict Europe has seen since 1945, CNN snapped into the type of all-hands-on-deck, boots-on-the-ground coverage that is the network’s bread and butter,″ Joe Pompeo observed for Vanity Fair. His take was grounded in the consensus of ‟the Twitter cognoscenti″ agreeing ‟that this is what CNN was made for″ and a welcome distraction from its own staff making the news themselves.

Pompeo reports that Discovery CEO David Zaslav praised CNN on a recent earnings call: “I’ve been watching a lot of CNN. This is where you see the difference between a news service that has real and meaningful resources globally, news-gathering resources, the biggest and largest group of global journalists of any media company, maybe with the exception of the BBC. … CNN is going to multiple correspondents and journalists risking their lives in Ukraine, in Poland, in Russia…with journalists in bulletproof vests and helmets that are doing what journalists do best, which is fight to tell the truth in dangerous places.”

READ MORE: CNN Goes All in on Ukraine as the Next Act in its Company Drama Begins (Vanity Fair)

Examples of brave people doing their jobs well is something that always gives this info-junkie hope. For example, watch the AP’s Philip Crowther do the news, in six languages for six different outlets.

Crowther’s efficient reportage was featured on News Nation Now’s America in the Morning, RTL’s De Journal, DW’s Noticias, Voice of America, Direct LCI and Servus TV’s Servus Nachrichten. As of Feb. 24, the video has been viewed more than 23.5 million times.

Ad Week broke down who’s where and reporting for which outlet. The Hill also put out a list highlighting anchors and correspondents on the ground in Ukraine.

But how does it feel to see these events play out on our screens? New York Times chief TV critic James Poniewozik writes about the cable’s Ukraine coverage: “If you are more than a few decades old, the invasion of Ukraine was horrific but familiar. It was what TV had taught you to expect since childhood.″

Poniewozik notes that “Even shock and awe eventually becomes a rerun″ with continuous coverage of the U.S.’ third war in as many decades. However, this time, “networks relied heavily on personal smartphone video, including, in a grim crossover, footage shot by the ‘Dancing With the Stars’ dancer Maksim Chmerkovskiy in Kyiv.″

He writes that this coverage is different because “This story was not simply one more skirmish in the endless cable war of words. This was war-war, as modeled by an international authoritarian movement flexing its muscle, executed by a country with a doomsday arsenal and ordered by a tyrant of questionable stability.”

Twitter also bristled when “grave images collided with TV business as usual. In a CNN clip, footage of air-raid sirens ominously sounding in Ukraine segued straight to the Zac Brown Band serenading glistening chicken pieces in an Applebee’s ad.”

Even so, “by Friday morning, [Ukraine coverage] was sharing space on American morning shows with stories about Covid policy and a busy upcoming wedding season. Avril Lavigne performed on ‘Good Morning America.’”

READ MORE: Ukraine on TV: We’ve Seen This Before. And We’ve Never Seen Anything Like It. (NY Times)

“Among the many times in which punditry can go very wrong, few rank as high as wartime. And nothing demonstrates that better than some corners of Fox News right now,″ Aaron Blake writes for the Washington Post’s The Fix.

Blake writes, “A number of its pundits and hosts have seen their statements on issues like sanctions contradicted by the network’s actual reporting on the situation″ and that’s a situation no journalist or news network wants to be in. And Fox News national security correspondent “Jennifer Griffin seems to have almost completely lost patience with all of it″ and has taken to live-fact checking of her colleagues and even questioned decisions to provide platforms for certain viewpoints — while live on the air.

Even as she refuses to mince words, Griffin insists her work continues in the same vein as it has for her 26 years with Fox. “

“I’m here to fact-check facts because I report on facts. And my job is to try and figure out the truth as best as I know it. I share those facts internally so that our network can be more accurate. That’s what I’ve always done.“

READ MORE: Fox News’s Jennifer Griffin Fully Loses Her Patience With Fox’s Ukraine Punditry (Washington Post)

Despite or perhaps even because of all the coverage, it can be easy to forget that there are real people whose lives are stake when you’re watching a war unfold from the comfort of your iPad. But for those with a personal connection to Ukraine, the constant deluge of information can be a blessing and a curse.

Jane Lytvynenko wrote about the experience of watching her hometown via livestream in the days leading up to Putin’s invasion for The Atlantic. On Feb. 23, Lytvynenko wrote, “What happens next isn’t clear, but I’ll be watching part of it unfold through a strange little portal on the internet. It helps.″

That portal was a livestream of Kyiv’s Maidan Square that Reuters shared to YouTube. It was one of many set up by wire services and networks tensely monitoring Ukraine as the world waited for Putin to act.

For Lytvynenko, a senior research fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, the video’s attraction was simple: ‟The stream of Maidan is different from all the noise. Nothing’s fake here; there’s no algorithm; and once I hide the live chat, there isn’t even a conversation to parse. It’s not a green screen against which TV pundits discuss Russia’s next move. The livestream is not trying to convince me of anything; it’s just showing me things as they are.″

Of course, that livestream has stopped now, and the square is no longer quiet. But Maidan is not a stranger to this eight-year-long conflict.

The livestream is not trying to convince me of anything; it’s just showing me things as they are.

Jane Lytvynenko, The Atlantic

‟Maidan is used to being filmed,″ Lytvynenko reminds us. ‟In 2014, social media was full of images of Kyiv on fire and determined protesters refusing to leave the square until the president left his post. Snipers opened fire on them eight years ago, almost to the day. … Signs of war and revolution are everywhere in Kyiv, but most of the world moved on after social-media streams filled with other news.″

READ MORE: I Can’t Stop Watching a Livestream of Kyiv (The Atlantic)

Why News Coverage of Ukraine Is Different

Even under peaceful circumstances, news in 2022 is sourced and informed by social media activity. The situation in Ukraine and Russia offers a more extreme example of that, with real-time reporting from the ground supplemented by civilian eyewitness videos posted to TikTok and Twitter commentators dominating the narrative for many new to observing geopolitics.

‟The Russian military launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. And the sources of information in this conflict are completely different from those in the Iraq War. The images and perspectives we’re seeing are dominated by smartphone videos shared on social media,“ journalist Mike Elgan writes via Substack.

And significantly, it “will be the first war to fully play out on social media. There will be no possibility of controlling the information” — as governments have always tried to do, in order to sway public opinion to their cause.

‟Unlike in the Iraq War, where the only cameras were controlled by a handful of journalists and the US military, the Russian invasion of Ukraine is taking place in a world where most people have video cameras in their pockets and can stream footage via social networks to a global audience,“ Elgan points out

The Russian invasion of Ukraine is taking place in a world where most people have video cameras in their pockets and can stream footage via social networks to a global audience.

Mike Elgan

Elgan writes that open source intelligence (which can be derived by parsing social media posts, among other techniques) ‟is the strongest and fastest method we have for disproving false-flag disinformation″ — especially pertinent in a war created by a former KGB agent’s conception of how the world should and shouldn’t work.

READ MORE: Here Comes the World’s First TikTok War (Mike’s List)

However, open source intelligence gathering and analysis poses logistical challenges for both reporters and tech companies.

Twitter has been the stage for many OSINT activities, but its human moderation team had been working under rules that unintentionally challenged some of these efforts. Tech Crunch’s Taylor Hatmaker reported that Twitter’s manipulated media policy resulted in some users being suspended for activity meant to help combat the Russian disinformation.

“We’ve been proactively monitoring for emerging narratives that are violative of our policies, and, in this instance, we took enforcement action on a number of accounts in error,” the company explained in a statement provided to TechCrunch, “We’re expeditiously reviewing these actions and have already proactively reinstated access to a number of affected accounts.”

Head of Site Integrity Yoel Roth weighed in (where else?) on Twitter:

READ MORE: Twitter Reinstates Accounts Sharing Open Source Info on Russian Military Threat (Tech Crunch)

It’s also worth cautioning individual social media users and news watchers (and journalists) that this is yet another situation in which what you see — or hear — isn’t always what you get. (Of course, that’s the often the case for your standard reel, let alone when an autocrat is actively attempting to control the narrative and spread disinformation.)

The Poynter Institute’s Al Tompkins offers a good tutorial for how to assess the veracity of video or images purporting to show the situation in Ukraine.

He explains the techniques journalists use and how to interpret metadata that accompanies digital files in ways that can be useful, but also reminds readers that there’s a necessary element of common sense and close observation that is still standard practice (like checking attendees’ watches to confirm the time a meeting was held).

READ MORE: How to Spot Video and Photo Fakes as Russia Invades Ukraine (Poynter)

Deadline’s Max Goldbart reported several significant media developments related to the war in Ukraine March 1.

First, a TV tower in Kyiv appears to have been struck by a Russian attack, which stopped temporarily halted broadcasts, according to local reports and confirmed by a statement from the Ukrainian parliament.

The Kyiv Independent’s live news feed reported that the attack killed five people and wounded five more. Later Tuesday, it announced that the following stations were back online: UA Pershiy, Rada TV, 1+1, Ukraina, ICTV, STB, Inter and Ukraina 24.

Elsewhere in Europe, regulators and tech and media companies are exploring their options in this information war.

Goldbart writes, ‟Google Europe announced it would be pulling Russian channels RT and Sputnik from Europe, effective immediately, and the EU is meeting later to discuss taking the same channels off linear TV throughout the continent. UK regulator Ofcom is currently investigating RT for breaches of impartiality.”

Several major movie studios also announced plans to either pause or pull movie releases from Russia, per Deadline.

READ MORE: Russian Air Strikes Hit Kyiv TV Tower; Channels Down In Ukraine (Deadline)

Meanwhile, in Russia, The Moscow Times reported in late February that ‟the Rozkomnadzor agency demanded that Russian media ‘use only information and data from official Russian sources’ in covering what it called the ‘the special operation connected with the situation in the Luhansk People’s Republic and the Donetsk People’s Republic.’”

However, the paper also noted that not all outlets were following the Kremlin’s instructions, writing that “Russian independent media, including the Meduza news website and the Dozhd television channel, had been covering the war using reports from the Ukrainian side, and from social media.”

Additionally, the paper reported on an editorial co-authored by 30 independent Russian media outlets as published by Meduza, which “declared opposition to ‘the massacre started by the Russian leadership’ and the ‘promise that we will be honest about what is happening while we have this opportunity.’” The authors also wrote, “We wish resilience and strength to the people of Ukraine who are resisting aggression and to everyone in Russia who is now trying to resist militaristic madness.”

READ MORE: Use Only Official Sources About Ukraine War, Russian Media Watchdog Tells Journalists (Moscow Times)

All of this had been preceded in Russia by months of state-sponsored propaganda, including as Columbia Journalism Review’s Jon Allsop put it: “State TV had teed Putin up by hyping bogus claims that Ukraine was shelling critical infrastructure, as well as heart-rending reports about the women and children who had to flee.”

But then there were the actual victims of violence and hate in Ukraine, and President Volodymyr Zelensky took to television in an attempt to appeal directly to the Russian people in their own language, despite the fact that Zelensky said, “They try to convince you otherwise. I know that Russian TV won’t show my speech. But citizens of Russia need to see it. They need to see the truth. The truth is you need to stop before it’s too late.”

READ MORE: Propaganda, Confusion, and an Assault on Press Freedom as Russia Attacks Ukraine (CJR)

Even in the midst of chaos and cruelty, social platforms ply their standard stock and trade. TikTok videos show the humanity of Ukrainians, soldiers and civilians alike, with a cheerful normalcy that is especially devastating in context.

This video of Ukrainian troops reminds us that the app’s bread and butter is trendy dances and makeup tutorials, not war footage.

A more hopeful take, of course, is that creators are always going to create, and Gen Z knows how to get the attention of the internet.

Also, reports of hacker collective Anonymous’ contributions to the war have yielded at least some surprisingly wholesome results. Apparently, their tweet forecasting cyberattacks included taking responsibility for swapping out Russian government propaganda on state broadcasters and government websites with programming such as Ukrainian songs, according to iNews reporting.

Some Aspects of Breaking News Are Always the Same

No matter what situation is unfolding, there are some inevitable or at least predictable elements.

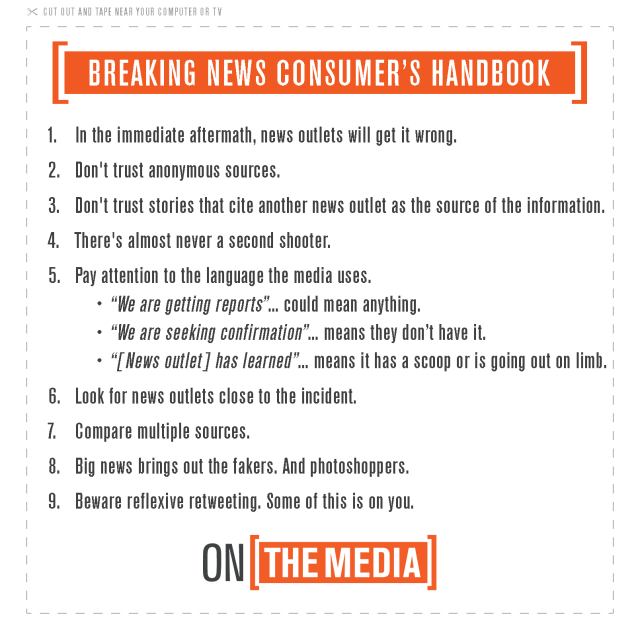

WNYC’s On the Media podcast created The Breaking News Consumer’s Handbook in 2013, and its advice has held up well, despite a decade of technological change and political turmoil. (Actually, the reminders are equally important for journalists and consumers in a world where much of the reporting is being sourced from social media.)

In the past, the show created editions specific to certain events or stories; as of March 1, they have not updated the project site to include information specific to the conflict in Ukraine.

Understanding the Context and the Crisis in Ukraine

Here are some informative articles (#longreads and otherwise) to help contextualize what’s happening in Ukraine and how the media has been covering the war:

- Kimberly St. Julian-Varnon explains what she thinks the Progressive Caucus Gets Wrong on Ukraine (it’s not a repeat of Iraq, for one) for Ice Cream Diplomacy.

- Journalist and Russian native Masha Gessen writes about visiting Russia’s sole remaining independent television broadcaster, TV Rain, as it covers the conflict in Ukraine. She filed for the New Yorker.

- The Economist editors write: History Will Judge Vladimir Putin Harshly for His War.

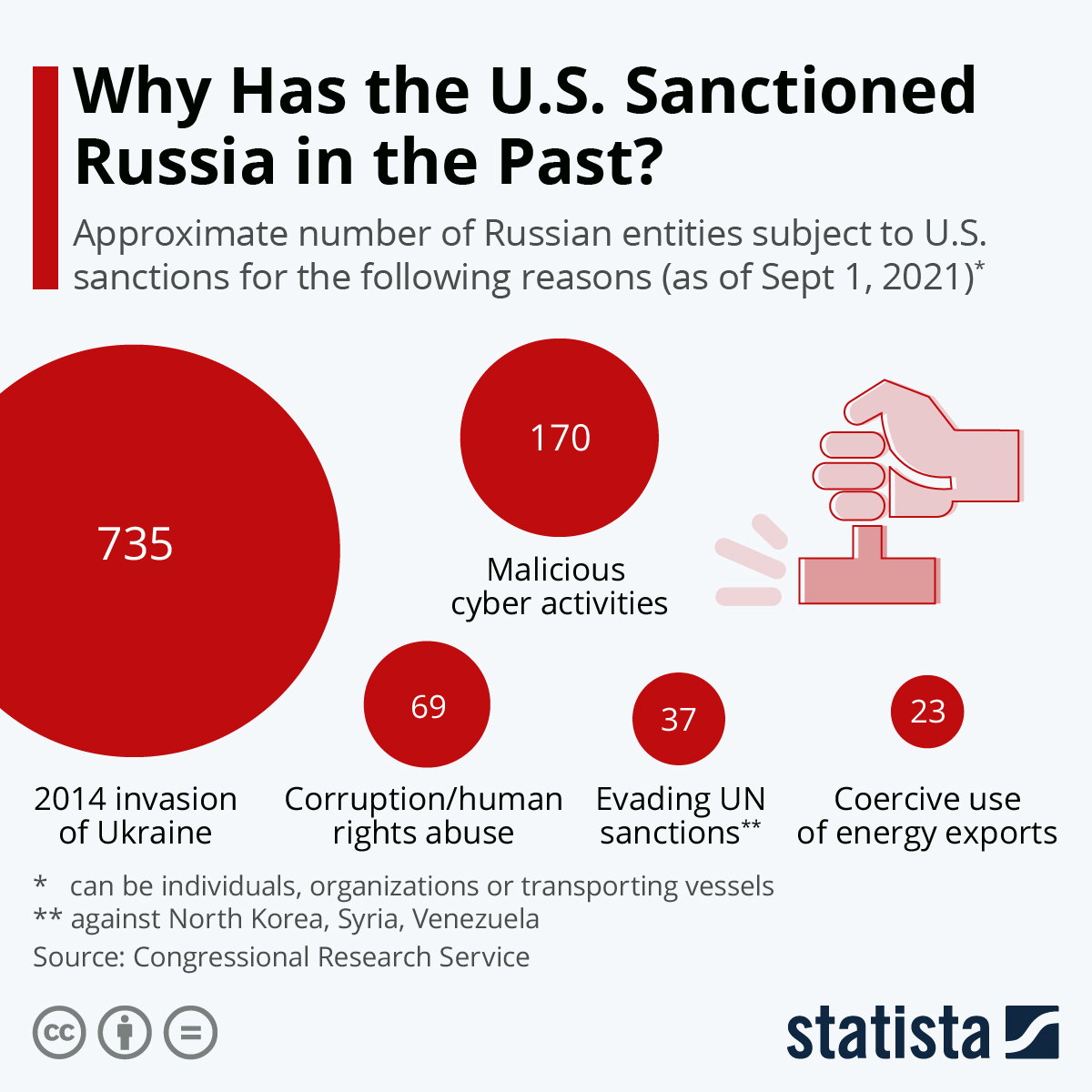

Much of the U.S. coverage has revolved around the American and European response to Putin’s actions, especially the unprecedented sanctions. Statista offers this helpful chart.

You will find more infographics at Statista

You will find more infographics at Statista

Then there’s Winter on Fire: Ukraine’s Fight for Freedom, a 2015 documentary focused on the Ukrainian civil rights movement that sprang from student protests against a Russian puppet government. It’s available to view on Netflix.

Watch this “making of clip” to learn what it was like to document “The Revolution of Dignity,” which some experts believe set the stage for Putin’s incursions into Crimea and the current conflict.

A more recent Russo-documentary and 2022 Sundance Film Festival favorite, Navalny follows Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny during his quest to prove the identity of his attempted assassin via nerve agent novichok.

Director Daniel Roher spoke to Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty about the process of making his film, which provides context about life in Vladimir Putin’s Russia and the difficulty of going against the president. Watch the interview below.