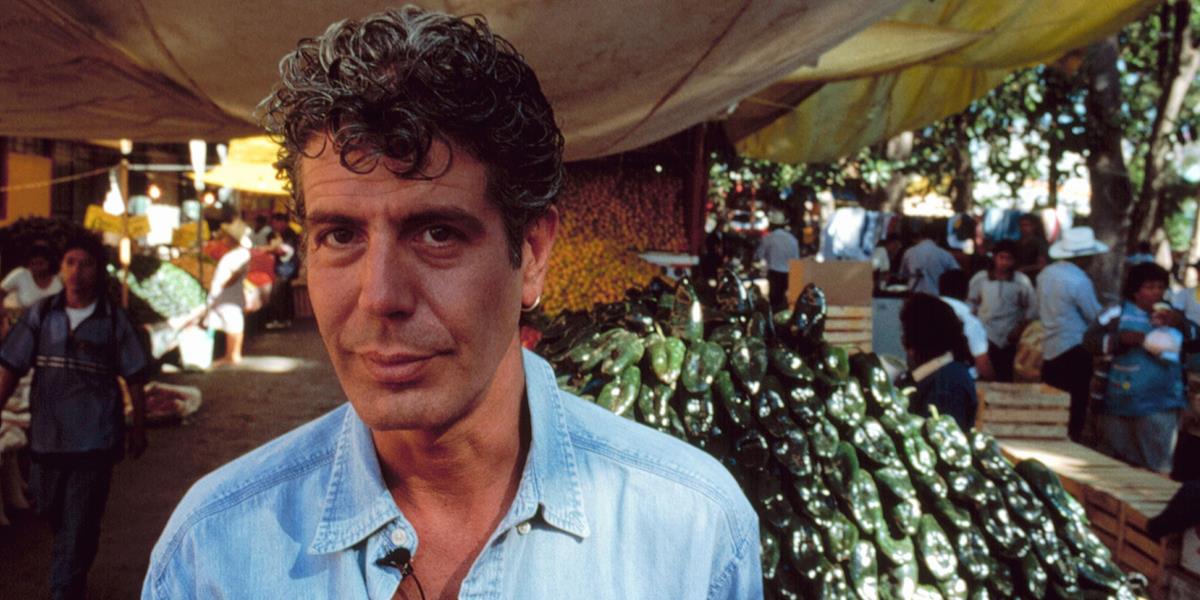

Oscar-winning filmmaker Morgan Neville’s new documentary Roadrunner: A Film About Anthony Bourdain is an emotionally gripping portrait of the widely beloved kitchen worker-turned-bestselling author and global television star who died by suicide in 2018, leaving behind grieving fans, friends and colleagues, and loved ones.

“You’re probably going to find out about this anyway, so here’s a little preemptive truth-telling,” Bourdain’s voice-over intones during the first few minutes of the film. “There’s no happy ending.”

Jason Sheehan, in his review for NPR, observes that Roadrunner doesn’t cover Bourdain’s rise to fame, which didn’t begin until he was in his 40s, “so much as the apex — stretched out across almost two decades. Here’s this guy, it says. He’s dead now, but you probably knew him. Or thought you did. Or believed you did. This is who he really was.”

Roadrunner “gathers the people who knew him best,” Sheehan writes. “Friends, partners, chefs, members of his team, his second wife, his brother. They’re all there to tell their stories, to explain him — and then admit that they never could. To laud him and say how much they loved him, and then dissolve into fury at his end.”

READ MORE: I Thought I Knew Anthony Bourdain. ‘Roadrunner’ Shows Us Who He Really Was (NPR)

The feature documentary, which is currently in theaters from Focus Features and will stream on HBO Max later this year, set a box office record in July for the biggest pandemic-era specialty release with a $1.9 million debut, according to Pamela McClintock at The Hollywood Reporter

Roadrunner’s performance at the box office is a much-needed boost for the specialty film business, McClintock notes, which has been hit particularly hard by the COVID-19 pandemic. Combined with the successful release of A24’s Zola and Fox Searchlight’s Summer of Soul documentary, Roadrunner’s achievement is another clear signal that cinema isn’t necessarily dead.

READ MORE: Box Office: Anthony Bourdain Doc ‘Roadrunner’ Sets Pandemic-Era Record With $1.9M Debut (The Hollywood Reporter)

NOT WHODUNNIT, BUT HOW-DUNNIT — DIGGING INTO DOCUMENTARIES:

Documentary filmmakers are unleashing cutting-edge technologies such as artificial intelligence and virtual reality to bring their projects to life. Gain insights into the making of these groundbreaking projects with these articles extracted from the NAB Amplify archives:

- “The Sparks Brothers:” A Musical Odyssey Turned Pop Art Documentary

- I’ll Be Your Mirror: Reflection and Refraction in “The Velvet Underground”

- “Navalny:” When Your Documentary Ends Up As a Spy Thriller

- Restored and Reborn: “Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised)”

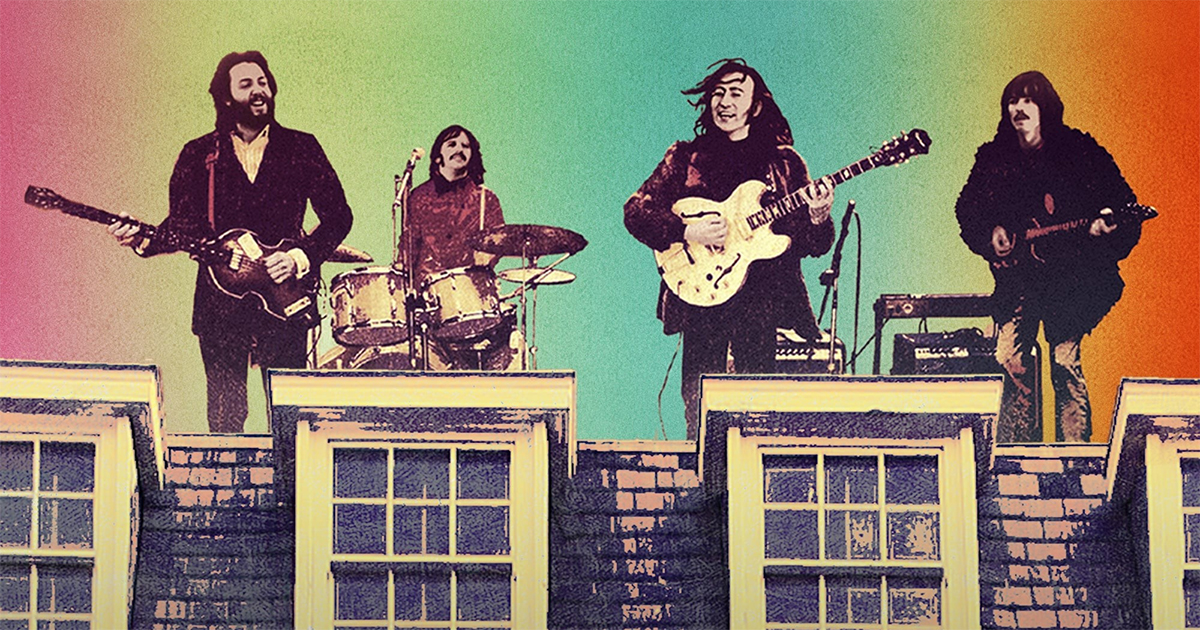

- It WAS a Long and Winding Road: Producing Peter Jackson’s Epic Documentary “The Beatles: Get Back”

The director, who won an Academy Award for 20 Feet from Stardom in 2014, and an Emmy for Best of Enemies in 2015, received critical acclaim for his Fred Rogers documentary, Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, in 2018. But Roadrunner became the subject of controversy almost immediately, after it was revealed that Neville had used artificial intelligence to recreate Bourdain’s voice for sections of the film.

Near the end of the film’s second act, artist David Choe reads aloud an email he had received from Bourdain. “Dude, this is a crazy thing to ask, but I’m curious…” we hear Choe read. Then Choe’s voice fades out and is replaced by Bourdain’s: “. . . and my life is sort of shit now. You are successful, and I am successful, and I’m wondering: Are you happy?’”

Asked how he had obtained a recording of Bourdain reading his own email in an interview with The New Yorker’s Helen Rosner, Neville disclosed that he had used AI to recreate the celebrated TV host’s voice. “If you watch the film, other than that line you mentioned, you probably don’t know what the other lines are that were spoken by the AI, and you’re not going to know,” he told Rosner. “We can have a documentary-ethics panel about it later.”

READ MORE: A Haunting New Documentary About Anthony Bourdain (The New Yorker)

The internet immediately exploded in outrage, with people posting hot takes such as “Well, this is ghoulish,” “This is awful,” and “WTF?!“ on Twitter, where Bourdain’s faked voice instantly became a trending topic. Film critic Sean Burns, who had already given the documentary a critical review, had one of the most damning tweets, writing, “I feel like this tells you all you need to know about the ethics of the people behind this project.”

When I wrote my review I was not aware that the filmmakers had used an A.I. to deepfake Bourdain’s voice for portions of the narration. I feel like this tells you all you need to know about the ethics of the people behind this project. https://t.co/7s1mdDOfzl pic.twitter.com/zv2pEvtTim

— Sean Burns (@SeanMBurns) July 15, 2021

The backlash was swift and unmistakable. “The idea that the filmmakers used AI to put words in a deceased person’s mouth is egregious. Unfortunately, the creeping use and abuse of this new technology in films and documentaries is becoming more prevalent — and it is unsettling, to say the least,” Christina Newland pronounced in iNews. “Manipulating AI and deepfake technology to raise the dead — who have no voices or consent to give — is at best distasteful, and at worst unethical.”

READ MORE: Manipulating AI to raise the dead, like Anthony Bourdain, is distasteful, unethical, and an insult to art (iNews)

“Later has arrived,” Andrew Limbong declared in an opinion piece for NPR, which includes a quote from Sheehan, who was unaware that Bourdain’s voice had been recreated for the film when he wrote his review. Sheehan wasn’t sure how he felt about the controversy, he told Limbong:

“I mean, is it all that different than Ken Burns having Sam Waterston read Abraham Lincoln’s letters in his Civil War documentary? Neville claims that he used Bourdain’s own words — things that he’d written or said that just didn’t exist on tape — and that matters,” Sheehan said, adding:

“If Burns had asked Waterston to make Lincoln say how much he loved the new Subaru Outback, then sure. That’s a problem. But this isn’t that. This is the (admittedly queasy) choice to bring back to life the voice of a dead guy, and make that voice speak words that already existed in another form. Is it creepy, knowing about it now? Absolutely. Was it wrong? I don’t think so. But these things are decided in public. It’ll get hashed out on social media and in spaces like this. And then we’ll move on, all of us having been forced to briefly consider the possibility of an endless zombie future where nothing we’ve ever said or written ever really goes away.”

READ MORE: AI Brought Anthony Bourdain’s Voice Back To Life. Should It Have? (NPR)

Neville described the process of recreating Bourdain’s voice using AI in an interview with Brett Martin for GQ. “We fed more than ten hours of Tony’s voice into an AI model,” the director recounted:

“The bigger the quantity, the better the result. We worked with four companies before settling on the best. We also had to figure out the best tone of Tony’s voice: His speaking voice versus his ‘narrator’ voice, which itself changed dramatically of over the years. The narrator voice got very performative and sing-songy in the No Reservation years. I checked, you know, with his widow and his literary executor, just to make sure people were cool with that. And they were like, Tony would have been cool with that. I wasn’t putting words into his mouth. I was just trying to make them come alive.”

READ MORE: What Was Anthony Bourdain Searching For? (GQ)

Helen Rosner, who broke the story in her interview with Neville, revisited the ethics of using AI to recreate Bourdain’s voice in a separate article for The New Yorker, writing that while she was surprised by the revelation, “Creating a synthetic Bourdain voice-over seemed to me far less crass than, say, a CGI Fred Astaire put to work selling vacuum cleaners in a Dirt Devil commercial, or a holographic Tupac Shakur performing alongside Snoop Dogg at Coachella, and far more trivial than the intentional blending of fiction and nonfiction in, for instance, Errol Morris’s Thin Blue Line.”

Ultimately, Rosner found the AI-generated audio to be less disturbing than the exclusion of Bourdain’s former girlfriend, Asia Argento, from the film. “I was more troubled by the fact that Neville said he hadn’t interviewed Bourdain’s former girlfriend Asia Argento, who is portrayed in the film as the agent of his unravelling,” she states.

“Documentary film, like nonfiction writing, is a broad and loose category, encompassing everything from unedited, unmanipulated vérité to highly constructed and reconstructed narratives,” Rosner continues:

“Winsor McCay’s short The Sinking of the Lusitania, a propaganda film, from 1918, that’s considered an early example of the animated-documentary form, was made entirely from reenacted and re-created footage. Ari Folman’s Oscar-nominated Waltz with Bashir, from 2008, is a cinematic memoir of war told through animation, with an unreliable narrator, and with the inclusion of characters who are entirely fictional.”

Compiling her own ethics panel, Rosner spoke with two experts — Sam Gregory, a former filmmaker and the program director of human-rights nonprofit Witness, which focuses on ethical applications of video and technology, and Karen Hao, an editor at the MIT Technology Review who focuses on artificial intelligence.

Both Gregory and Hao agreed that the two core issues with the Roadrunner controversy were consent and disclosure.

“If you look at a Ken Burns documentary, it doesn’t say ‘reconstruction’ at the bottom of every photo he’s animated. But there’s norms and context — trying to think, within the nature of the genre, how we might show manipulation in a way that’s responsible to the audience and doesn’t deceive them,” said Gregory.

“There are really awesome creative uses for these tools, but we have to be really cautious of how we use them early on,” said Hao, pointing to the re-creation of the late Marcia Wallace’s voice for The Simpsons character Edna Krabappel as an ethical use of the technology.

“You know that the person’s voice is not representing them, so there’s less attachment to the fact that the voice might be fake,” she said, adding that in the context of a documentary, however, “You’re not expecting to suddenly be viewing fake footage, or hearing fake audio.”

READ MORE: The Ethics of a Deepfake Anthony Bourdain Voice (The New Yorker)

“Have documentaries evolved to the point where the very term ‘documentary’ has lost all meaning?” Ann Hornaday asked in an opinion piece for The Washington Post:

“The idea that what we thought was Bourdain’s voice was, in fact, a deepfake elicited gasps among purists, as well as some of Bourdain’s passionate fans, who expressed feelings of betrayal and even trauma at having their idol posthumously exploited. Although Neville insists that he had the permission of Bourdain’s former wife and literary executor to make the AI recordings, Ottavia Bourdain issued a tart statement disavowing her cooperation: ‘I certainly was NOT the one who said Tony would be cool with that,’ she tweeted.”

But Hornaday goes beyond the outrage du jour, examining the place of truth in documentary filmmaking. “Technically, a documentary is so called because it documents events as they unfold. But, contrary to conventional wisdom, documentaries are never mere recordings of reality. On some level, they always lie, or at least bend the truth — which doesn’t always mean they’re dishonest,” she writes.

Ultimately, Hornaday maintains, it’s up to audiences to remember that documentaries aren’t journalism. “They’re art,” she says. “Although nonfiction filmmakers use journalistic tools such as interviews, research and acute observation, they aren’t reporters but storytellers, who will go to any lengths necessary to engage their audience not just through information, but emotion.”

The uproar over Bourdain’s AI-generated voice “is but the latest iteration of an argument that has attended the nonfiction genre throughout its evolution,” Hornaday asserts:

“That debate goes as far back as 1922, when Robert Flaherty released the silent film Nanook of the North, a portrait of an Inuk family in the Canadian Arctic that contained staged scenes of the protagonist hunting and interacting with a White fur trader. In 1988, Errol Morris revolutionized the form with The Thin Blue Line, a riveting true-crime procedural in which he used stylized, slow-motion inserts and re-creations to heighten dramatic tension.:

Hornaday argues that Neville could have avoided controversy “simply by disclosing the fact that a few lines in Roadrunner were produced in a computer rather than spoken by Bourdain,” in the film’s opening or closing credits.

The best examples of this kind of transparency, Hornaday contends, can be found in projects like Sarah Polley’s 2012 documentary, Stories We Tell, which interweaves interviews and documentary footage with reenactments and more speculative material, all “skillfully disentangled” at the end of the film to reveal her creative process. “It’s a gesture that simultaneously reflects Polley’s confidence as a director and a deep respect for her tacit contract with viewers for whom the word ‘documentary’ entails the expectation that, even if what they’re seeing isn’t the whole ‘truth,’ at least they won’t be tricked or purposefully deceived,” she writes.

“It’s that contract that led Heidi Ewing — best known for the nonfiction films she has co-directed with Rachel Grady — to insist that her latest production, I Carry You With Me, be called a narrative feature, not a hybrid (and certainly not a documentary),” Hornaday continues. “The film tells the story of two real-life men who met in Mexico and eventually moved to the United States; Ewing cast actors to play them as children, dramatizing early events of their lives, creating composite characters and adding imaginary scenes. Although the actual protagonists appear in I Carry You With Me, Ewing says, she had no doubt what category the film belonged in.”

READ MORE: The controversy over Anthony Bourdain’s deepfaked voice is a reminder that documentaries aren’t journalism (Washington Post)

Neville defended the re-creation of Bourdain’s voice for his film, telling ABC News, “It was a modern storytelling technique that I used in a few places where I thought it was important to make Tony’s words come alive.”

Carolyn Giardina, tech editor at The Hollywood Reporter, also weighed in, commenting, “It’s very sensitive because Anthony Bourdain obviously had a tragic death. This and similar uses, I think are going to continue to be a gray area for quite some time.”

But criticism about Roadrunner didn’t focus solely on the digital re-creation of Bourdain’s voice. The voice of Bourdain’s last romantic partner, Asia Argento, is missing from the film even though she figures prominently in the wrenching final act, and the perceived implication that she had somehow been responsible for Bourdain’s death has drawn ire.

Speaking again to Brett Martin at GQ, Neville admitted that he hadn’t attempted to contact Argento. “I didn’t. Just because I feel like the complication and weight of her part of the story could capsize the film in a heartbeat,” he explained, adding:

“It’s so complicated. And I felt like it wasn’t actually going to teach me any more about Tony. Whenever I started to bring in more of the story, it just made people ask ten more questions, which weren’t interesting questions. They were just, like, What about this? How did that happen? Somebody else can make that movie.”

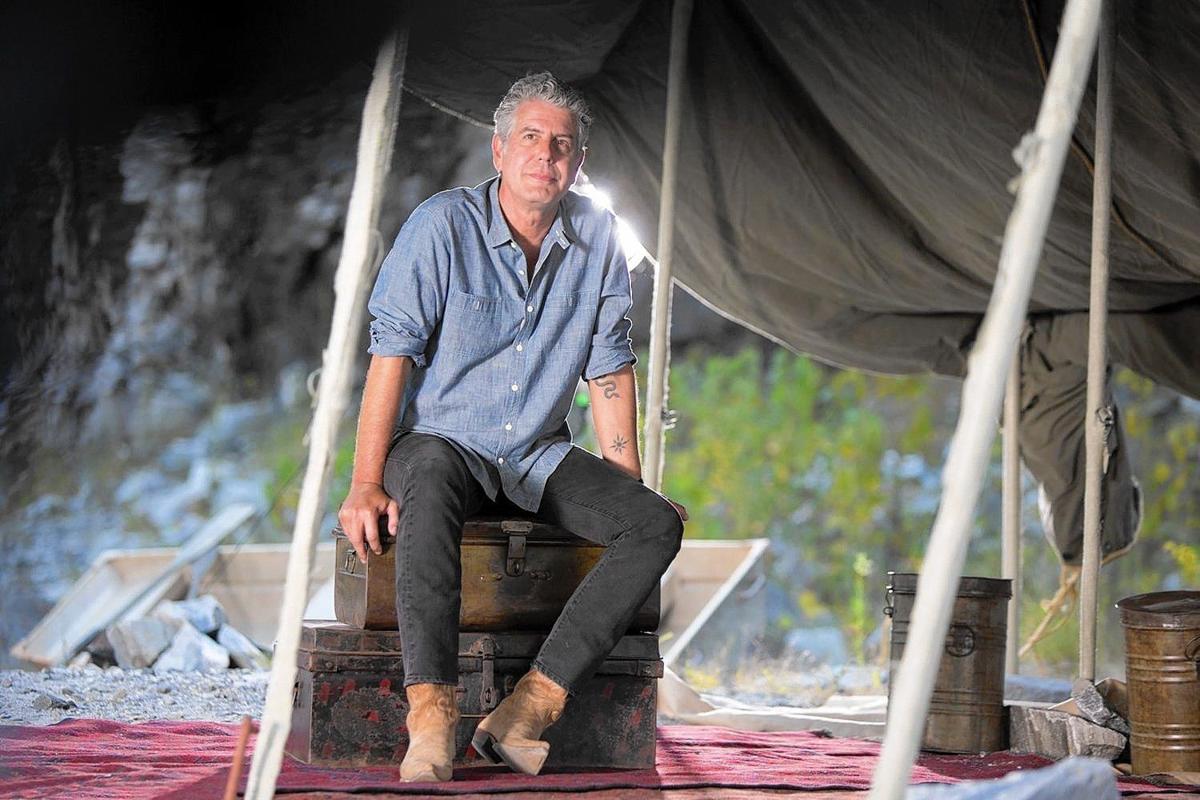

Using all of the filmmaking techniques at his disposal, Neville sought to create a portrait of a complex man who was adored but not necessarily liked, and who wrestled with his own self-destructive impulses. Bourdain also grappled with his contributions to “toxic male kitchen culture” inspired by his book Kitchen Confidential, and the complications of filming in underdeveloped nations as if he was introducing them to the world.

“I think he was definitely aware of a kind of sell-by date for the white ‘colonial’ voice telling people what’s interesting,” Neville told GQ. “I really think… that Tony would have been thrilled if he could not be in his show. He didn’t want it to be about him, but that became kind of the price the public demanded of him in order to do it. He definitely worried about who was benefitting from what he was doing.”

At one point Roadrunner draws a parallel between Bourdain’s trip to the Congo and Apocalypse Now, a creative choice Martin asked Neville to explain. “That story, to me, was about, ‘Is he Willard or is he Kurtz?’ Is he the rational journalist? Or is he the one who has become the protagonist and gone insane?” Neville said:

“I feel like that’s the dialectic he wrestled with whether the story took place in the Congo or anywhere. I actually think that episode is one of the best depictions of life in central Africa that’s ever been on American television, but that’s the part I was leaning into and, yeah, it’s dancing up against some pretty racist tropes.”

READ MORE: What Was Anthony Bourdain Searching For? (GQ)

In her review for Vox, Alissa Wilkinson writes that her eyebrows raised a few times during the film and as she considered it afterward. “I am bothered by the section that involves Argento — it veers disturbingly close to outright blaming her for Bourdain’s death,” she says. “Most likely, it’s his friends’ attempt to find a cause for his death, but that’s an ill-advised way to grapple with death by suicide. Bafflingly, Neville has said he didn’t ask Argento to participate in the film, which would have been a lot more fair to her, and the decision to exclude her without informing viewers raises some acute ethical questions.”

READ MORE: The new Anthony Bourdain doc is ethically thorny but worth watching (Vox)

Writing for The Ringer, Alison Herman notes that toward the end of the film Neville includes a “disclaimer of sorts” in the form of Michael Steed, who served as a producer on Bourdain’s shows No Reservations and Parts Unknown. “I don’t want to, like, blame the girlfriend, or blame the lover, or blame the husband,” Steed says in the film. “Tony killed himself. Tony did it.”

That Steed is just one of the many close associates Neville interviews, a group that spans Bourdain’s friends, family, and colleagues, makes Argento’s exclusion all the more damning. “Roadrunner’s guest roster is so comprehensive that Argento’s absence is especially obvious,” Herman writes, adding:

“The interlude is both uncomfortable and necessary; without it, Roadrunner would walk right up to the line of doing exactly what Steed says he wants to avoid — linking Argento to Bourdain’s downward spiral. But by not giving Argento herself a chance to appear or even respond to the film’s contents before its release, Roadrunner essentially drifts across the line anyway.”

READ MORE: The Double-Edged Ethics of the Anthony Bourdain Documentary ‘Roadrunner’ (The Ringer)

Want more? Roadrunner director Morgan Neville shared an expansive playlist containing some of Bourdain’s favorite songs with Rolling Stone. The playlist fittingly starts with the Modern Lovers classic “Roadrunner,” and goes on to feature an range of selections from artists like the Beach Boys, Talking Heads, Iggy Pop, the Stooges, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, Marvin Gaye, Rosa Yemen, Joy Division, the Velvet Underground, Hank Williams, Parliament-Funkadelic, Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes, and Bob Dylan.