Kenneth Branagh’s evocative semi-autobiographical coming-of-age story set in 1969 is shot “to feel like a Life magazine spread,” according to cinematographer Haris Zambarloukos, BSC, GSC.

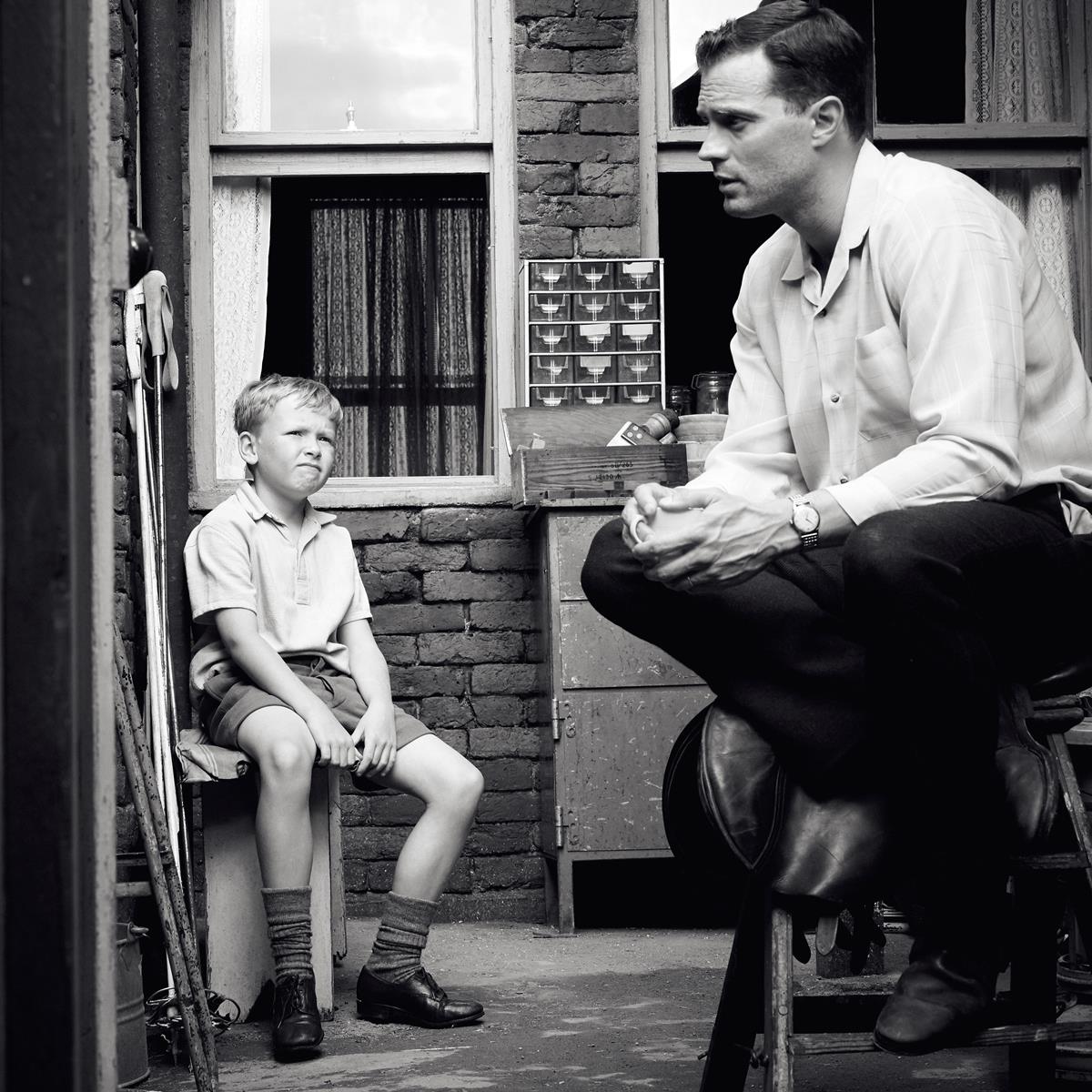

Belfast is Branagh’s lived experience of Northern Ireland as expressed through nine-year-old Buddy (Jude Hill). He lives with his Ma (Caitriona Balfe) and Pa (Jamie Dornan) and near his Granny (Judi Dench) and Pop (Ciarán Hinds). It’s a poem to his immediate family and to the city which is depicted as a close-knit community on the verge of being shattered by three decades of violence and sectarian division.

“This film is about the human condition and the landscape of the human condition is the human face,” says Zambarloukos, who has worked with Branagh since Sleuth on projects including Cinderella and Death on the Nile. “The methodology here was how do we create great portraits. I think black and white has a very transcendental quality. It can be two things at the same time. It can illustrate the within and the without simultaneously and seems to talk to both the present and the past very easily and more so than color.”

Up until the 1970s, action-adventure films were given the Technicolor treatment while smaller scale drama were predominantly shot black and white. “In that sense we’re not doing anything different to how B&W has been used in the past,” he says.

Mixing Color and B&W

“There is something really lucid and clear and at the same time ethereal and mysterious inherent in black-and-white photography. I feel color is often better at being descriptive — you can see it’s autumn because of the red leaves in shot. But since filmmaking tends to be about narrowing the focus for the a udience, about how and where they see things, black-and-white is a fantastic way of capturing emotion.”

The film opens in color and also flashes into color for scenes showing Branagh/Buddy’s love for cinema as a child. Raquel Welch in a fur-skinned bikini in One Million Years B.C. and the flying car of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang leave strong visual and emotional imprints.

It’s not the first time Branagh has combined B&W with color. His directorial debut feature Dead Again (1991) contained flashbacks to 1940s Hollywood in black and white. The opening scene of Death on the Nile, which finally gets its cinema release in the New Year, is black-and-white but shot in color.

Shooting black-and-white in color was the DP’s preferred option for Belfast. “One thing I like about always seeing things in color is that I have far more control over skies,” he explains. “If I lose the color in the sensor, in the DI, or in the capture then if it’s film neg I can’t then give those colors a more precise grey tone.

“In the DI, especially with black-and-white, I like to be able to assign where in the grey scale something is whether that’s a sky, clothing, a face. By having color you can key it, matte, it and be more precise.”

That is a technique inspired by master photographer Ansel Adams. In his books, The Camera, The Negative, and The Print (published 1948-50), he talked about assigning tones of grey in a zone system “and seeing a picture before you take it.”

Zambarloukos says, “Those seminal books were for analogue black and white stills of the time but you can take those principals and apply them to modern photography and a DI. In essence, as long as you see it, you can control it.”

The DP’s digital imaging technician and dailies team was led by Jo Barker at UK facility Digital Orchard. Goldcrest colorist Rob Pizzey handled the DI. “Our dailies are more contrasty than the final film,” Zambarloukos says. “A lot of our tests were about capturing texture and weave. I don’t think we manipulated things to an extreme in the end but it was nice to have the control to bring things down or up if we needed.”

Magnum Composition

Zambarloukos says he often finds tonal and compositional cues from the work of Magnum photographers. For Belfast, he found the work of Welsh photojournalist Philip Jones Griffiths illustrative of the era.

“In his images he showed a juxtaposition of family and military life. There’s a really famous one of a woman mowing her lawn with a solider in the foreground. It was this depiction of conflicting things in an image that we wanted to achieve photographically with Ken.”

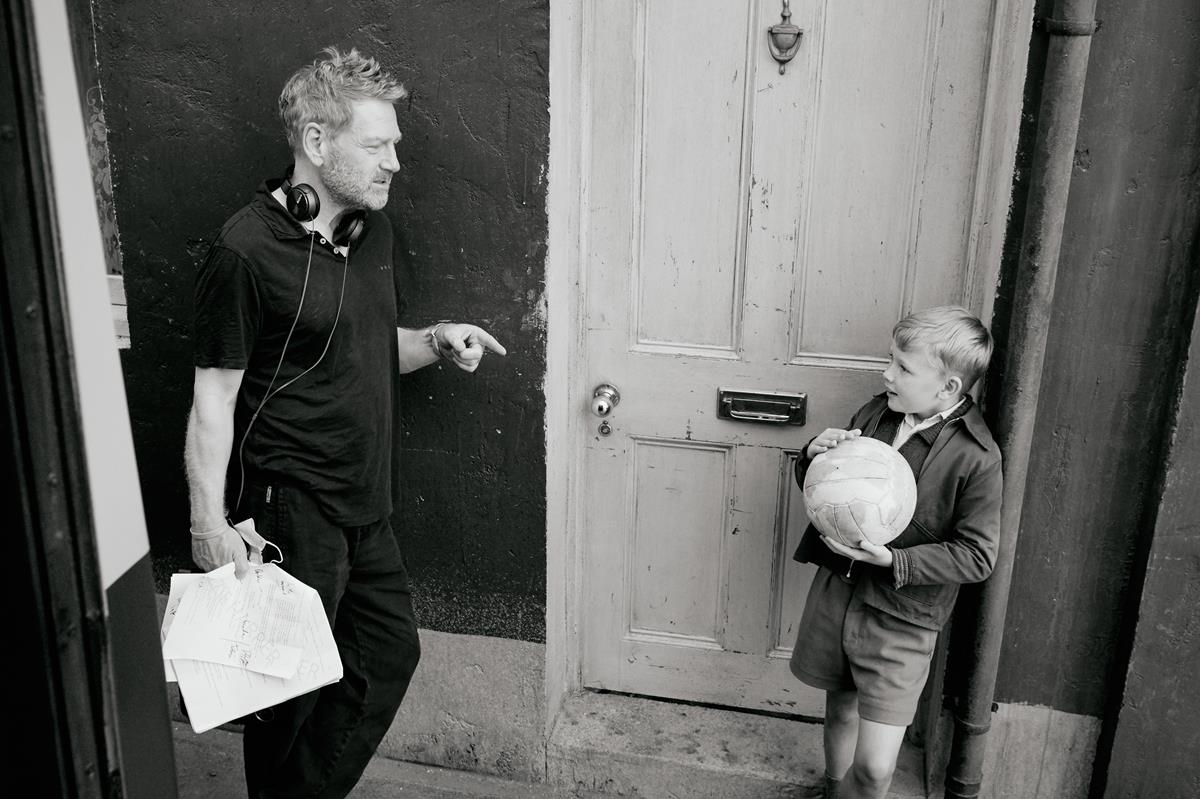

This idea informed their use of camera and composition. The riot scene was shot handheld with two cameras and included an elaborate set up on a circular track around Buddy for the Molotov cocktail explosion at the film’s beginning. Mostly, the film is shot single camera with Zambarloukos feeling that he should be quite still in his composition “and leave space to allow the film to breathe.”

This pared-down approach relies on the director’s ability to block the mise en scène. “Ken is such a master of knowing where to place actors and how he wants them to interact. In this case, less is more. There’s a stillness to the action and I think that slightly wider framing helps in that way.

“I try to give [editor Una Ní Dhonghaíle] really direct eyelines so that when you do let a scene play like that then the character’s face, their eyeline, is as much as possible not facing away from camera or too much in profile. There is a directness. We try and choregraph with the camera to close the eyeline as much as we can and by doing so we are hopefully being engaging, inviting and immersive.”

In an interview with Dolby, Branagh reflects on the film, saying “We’ve been lucky to work on things where story and screenplay are good. And if that’s the case, then the imaginations of the audience take over. It’s a beautiful thing to be, to be part of. And in Belfast, I think it takes you to that place and takes you on that young man’s journey with even greater personal involvement.” Watch the full conversation in the video below:

Shooting Digital

Branagh and Zambarloukos typically shoot on film, yet this is the first picture they’ve made together on digital. There were a number of reasons for this, among those was that the production was among the first in the UK to shoot under COVID, in August 2020.

Anything the production could do to minimize personal contact in the space was put into effect. Changing film magazines being one casualty. Zambarloukos also operated for this reason too (with Andrei Austin on Steadicam).

It wasn’t just a COVID-enforced decision, though. Branagh wanted the freedom to shoot longer takes. Most importantly, digital suited the creative aesthetic.

“We wanted to shoot available light using either practical’s or with a set designed so that the windows faced sunlight. We blocked so our actors would sit near windows. Rather than a documentary film we went for a photo reportage look so it felt natural to use the high ASA rating of the Alexa LF. The LF Mini is a game changing camera. It has a nice soft palette yet is crystal sharp and clear. With that medium format digital we found a sweet spot.”

LIGHTS, CAMERA, ACTION! SPOTLIGHT ON FILM PRODUCTION:

From the latest advances in virtual production to shooting the perfect oner, filmmakers are continuing to push creative boundaries. Packed with insights from top talents, go behind the scenes of feature film production with these hand-curated articles from the NAB Amplify archives:

- Savage Beauty: Jane Campion Understands “The Power of the Dog”

- Dashboard Confessional: Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s “Drive My Car”

- “Parallel Mothers:” How Pedro Almodóvar Heralds the New Spanish Family

- “The Souvenir Part II:” Portrait of the Artist As a Young Woman

- Life Is a Mess But That’s the Point: Making “The Worst Person in the World”

He retained the large format 65mm lenses used on Death on the Nile and Murder on the Orient Express, a mix of older Spheros from the David Lean era and System 65 glass made for the format’s resurgence in the early nineties on films like Ron Howard’s Far and Away (1992) and Branagh’s Hamlet (1996).

“I found that combination worked really well especially in 1.85:1. It’s the first time we’ve shot in that aspect ratio instead of 2.39:1.”

Production Economy

The crisp image is a deliberate choice. “I didn’t use diffusion or add grain or denoise it. It is pretty much what you see out of that sensor and those lenses.”

Branagh’s regular production designer, Jim Clay, designed in accordance with COVID-safe rules and the intended aesthetic. For example, there were discussions about keeping set windows open for ventilation.

The sets were built in southeast London near Longcross Studios where Branagh and his keys were polishing Death on the Nile. An unused school site was used to build the film’s school, hospital, and church. The fields around it — including a basketball court — are also featured. The interior sets of the houses were built here too, without back or front and covered by canvas as weather protection. At the nearby Farnborough airfield they built the façade of the terrace house fronts and redressed that street to film scenes for Ma and Pa’s street or Granny and Pop’s street or a third street occasionally seen. The riot was filmed there too.

“The cinema and theatre were chairs, a small screen, black drapes and a projector in one of the airfield hangers,” says Zambarloukos. “That hanger was also where we placed our bus to film rear projection in camera for the bus journey from the theatre. There’s a real economy to this but I think we built to the scale required.”

The themes of the film resonated with many of the cast and crew who could relate personally to the humanity of everyday people and the political forces of division. Zambarloukos for example, is a Greek Cypriot and recalls the Turkish invasion of the island in 1974.

“I was four years old and my father had to seek work abroad [Branagh’s family also emigrated]. Belfast could easily be a Cypriot story. It’s clearly a universal story. Ken is writing about finding joy in the sorrows of life. If such circumstances happen to you, you have a choice how to live your life and the choice’s Ken’s family made are some of the best you can take.”

Want more? In the audio player below, listen to Branagh discuss the making of Belfast on Vanity Fair’s Little Gold Men podcast, including what it was like to finally see the film play before a live audience.

Branagh called the experience “amazing,” noting the immediate impact Belfast had on those who may not even be aware of Northern Ireland’s history. “What seems to connect is family, people’s recognition of some of the difficult choices in the film that have to be made by the family — and also a kind of empathy or recognition of the moment in the boy’s life, our nine-year-old leading character, who is at a point where innocence is lost,” he said. “In a way, the film is about a moment that registers [when] we begin to see the last day of his childhood, if you like. [There’s] the beginnings of the bruising process of becoming an adult and dealing with the issue of loss, whether it’s the loss of a family or a home or an identity or whatever.”

Branagh also spoke with IndieWire, calling Belfast his most personal film yet. He also explains how making the film allowed him to revisit and relive his childhood experiences from the 1960s:

In an interview with Bill Maher, Branagh delves into his memories of tribalism and how it led to violence in Northern Ireland:

Watch this exclusive commentary from Branagh as he explains how this collection of scenes were inspired by his own personal childhood experiences:

But even though the film is set in Ireland in the 1960s, “Ken made it very clear that we’re not making a film about the troubles in Belfast,” says director of photography Haris Zambarloukos. “We’re making a film about a family, and how they, deal with the outside world and what do they bring into their home and how did they shield that home and how do you shield childhood.”

In the video below, learn how Zambarloukos worked to help bring Belfast alive within a very small visual world:

The opening scene of 8 1/2, probably the best autobiographical film ever made: