The UK’s Digital Production Partnership (DPP) has published the first report in its Going Live & Remote series, entitled “Live Remote Production.” Drawing on the input of 60 experts from across the industry, the research solves a fundamental problem facing producers: the fact that there is no agreed definition of remote production.

The report defines, for the first time anywhere, five architectural models for producing live content, and was enabled by lead sponsor Atos, expert sponsor Ross Video, and contributing sponsors Kiswe, and Telstra.

In his foreword, Ross Video CEO David Ross wrote, “Sometimes it takes unexpected events to make us look at life a little differently. Just over a year ago we were all getting on with business as usual — preparing for trade shows, planning product launches and discussing new projects with customers, all blissfully unaware of the calamity that was about to knock everything sideways.

“In the early days of the pandemic, the media production industry’s gaze turned almost wholesale towards solutions and tools that would enable remote collaboration and production. I think we all knew that remote production was going to become the norm, but we imagined the adoption and transition as a gradual, orderly and considered process rather than the mad scramble we actually experienced.

“Now, as we slowly emerge from the grip of the pandemic, it’s clear that it has acted as a catalyst for remote production principles and cloud-based solutions. They do say that necessity is the mother of invention, and the last twelve months have seen the emergence of innovative new tools to enable collaboration and contribution to continue, with low latency and high production values very much at their heart.

“If there is one silver lining to take away from this dreadful experience, it will be that resilience and innovation. After all, the show must go on…”

Defining Which Production Model will be Dominant in Coming Years

By focusing on foundational technology and workflow components, the remote production models outlined in the DPP report are applicable to content as diverse as sports, news, esports, entertainment, and corporate events.

“When talking to industry professionals about remote production, it quickly became painfully clear that terminology is a key problem, so we started by addressing that,” said DPP CTO and report author Rowan de Pomerai. “And it’s remarkable what that unlocks. By defining the production models, we were then able to examine the benefits of each, and see clearly which will be dominant in the coming years.”

The report enables companies not just to understand the state of the art, but also to anticipate which models best suit their present and future needs. It assesses each production model against factors such as: content and creative opportunities; bandwidth and latency sensitivities; cost and risk management.

“Our expert contributors provided insight into both the challenges and opportunities unlocked by different live remote production architectures,” added de Pomerai. “They also shared their plans for the future. While 2020 saw a dramatic rise in Distributed production, we predict that Centralized and Cloud production will dominate in the longer term.”

On Location; Remote Controlled; Centralized; Distributed; and Cloud

For the first time, the DPP has identified five clearly defined models of live production.

On Location: The traditional model in which content acquisition, signal processing and production control are co-located, whether at a studio complex or an outside broadcast. It is the baseline by which other models are judged, using tried and tested workflows that enable production teams to work closely together and maximize creativity.

Remote Controlled: Remote controlled production moves the control surfaces and operators to an offside location such as the broadcaster’s headquarters, while keeping processing at the acquisition site. This approach has been popular during the pandemic to improve social distancing but also has broader applications in reducing crew travel, while making use of existing outside broadcast equipment and infrastructure.

“While 2020 saw a dramatic rise in Distributed production, we predict that Centralized and Cloud production will dominate in the longer term.”

— Rowan de Pomerai

Centralized: This model moves the signal processing and production control to a central hub location, such as the broadcast center. A great deal of bandwidth is required to transport all the audio and video feeds from the acquisition site, but the model delivers higher utilization of equipment and crew, lower capital investment and lower carbon footprint.

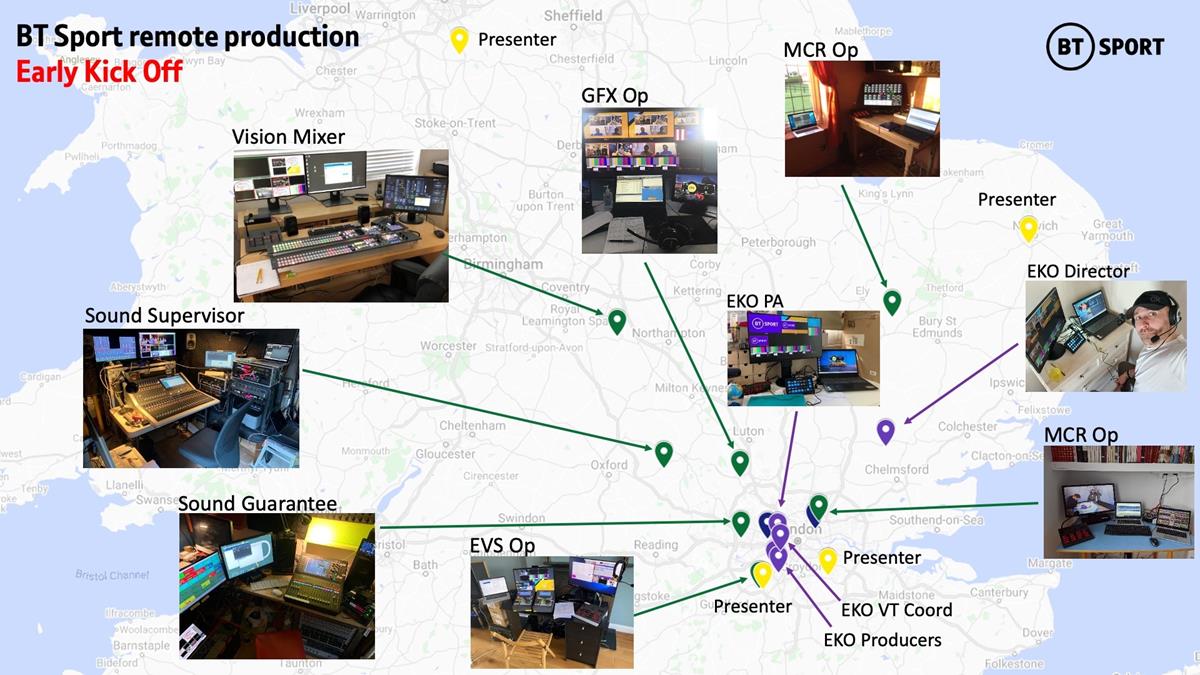

Distributed: This architecture also usually involves centralized signal processing, but offers flexibility by enabling crew to remotely control the production from multiple production hubs, or even from home. It adds complexity to the connectivity provision, but in return it offers the potential to reduce travel even further, while opening up access to the best talent no matter where they are.

Cloud: The final option locates some or all of the signal processing in the cloud, controlled remotely from production hubs or from home. It offers similar benefits to distributed production, with additional flexibility and scalability, and lower capital costs. As the capability of software production tools improves rapidly, cloud production will join centralized production as a dominant model.

Content, Bandwidth, Latency, Cost… and Risk

What is the right type of remote? Having defined five key models of live production, the report examines the reason why a production might choose one over another. There are four primary constraints and considerations that were raised repeatedly during discussions with the expert contributors: content, bandwidth, latency and cost.

Content: Whichever production is chosen must serve the goals of the content being produced. Despite a general enthusiasm for remote production, on location production was the most commonly chosen answer.

However, a close second was centralized production, reflecting a feeling that production teams work best when they are physically together, whether at the acquisition site or a separate production hub.

Bandwidth: The bandwidth available to the acquisition site will have a significant impact on the production architectures that can be employed. Remote controlled production is possible with relatively low bandwidth, while centralized production requires considerably greater connectivity. Distributed production relies upon the available bandwidth to each production hub and/or to the crew’s homes.

Latency: This is the delay introduced into the signal path either by the time taken for a signal to traverse the network, or by signal processing. It affects all of the remote production models, as latency can be problematic for both control signals and media streams.

While latency can be carefully managed and reduced to a certain extent, it is ultimately governed by the speed of light; there is a theoretical minimum time for light to travel along a fiber optic cable between two points. As a result, the latency involved in a remote production will differ depending on the physical distance between the acquisition site and the production hub.

Cost & Risk: Alongside creative and technical constraints, cost is a crucial factor in choosing a remote production model. There are too many variables at play for it to be possible to give a simple answer to the question, which architecture costs least? But when asked, the DPP experts gave strong indications that for a new build, centralized and cloud production have the potential to be the most cost efficient.

At times, the report concludes, it can be challenging to learn new workflows, new ways to communicate, and new tools. But for every challenge comes a new opportunity. An opportunity to deliver a better production at lower cost. An opportunity to reduce the environmental footprint of our industry. Or an opportunity to produce coverage of an event a thousand miles away, and be home in time to put the children to bed.

The content for the report was gathered through a series of workshops and interviews with experts from across the industry, who included Roelend Awick, Project Manager, RTL; Rich Baker, Senior Broadcast & Multimedia Manager, Formula E; Narinder Ball, Outside Broadcast Operations Executive, BT Sport, Charlie Cope, Technical Executive, BBC Sport; Tom Copeland, Head of Broadcast Technology and Technical Operations, Sunset + Vine; Bevan Gibson, CTO, EMG; Wendy Hendrickx, Head of TV Production, Formula 1; Steve Kruger, Head of Technology – Entertainment, ITV Studios; Kevin McCue, Director of Technical Operations, Sky Sports; Marc Segar, Director of Technology, NEP; and Willem Vermost, Design & Engineering Manager, VRT Belgium.