The disappearance of Saudi Arabian dissident and Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi shocked the world in October 2018, unfolding in a months-long murder investigation filled with grisly details that ultimately exposed a global cover-up by the royal family. The gruesome assassination — along with Saudi Arabia’s efforts to control international dissent — is the subject of a gripping new documentary, The Dissident, directed and produced by Bryan Fogel.

Impressing audiences during its world premiere at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival, The Dissident exerts storytelling power, using cinematic editing, pacing and cinematography to lead viewers through the complex narrative. “With lots of information on spycraft and surveillance, The Dissident plays out more like a thriller,” Michael O’Sullivan writes in his review for the Washington Post.

READ MORE: The new documentary on Jamal Khashoggi’s murder plays out like a spy thriller (Washington Post)

Fogel, who previously won an Academy Award for his 2017 documentary Icarus, draws inspiration from filmmakers like Christopher Nolan and Paul Greengrass, “who employ classic cinematic techniques to build tension through the use of sound, music, graphics and design to engage the audience,” as Anna Marie De La Fuente writes in Media Play News.

“If you can engage audiences through the storytelling, those great cinematic techniques will shine through and make people care about the story and its characters, and if they do that, then perhaps there lies the ability to bring about change,” Fogel said to De La Fuente.

READ MORE: Talent Talk: Oscar-Winner Bryan Fogel Sheds Light on the Murder of Saudi Journalist Jamal Khashoggi in ‘The Dissident’ (Media Play News)

“The film opens like a suspenseful 1970s crime thriller, under grey skies of Montreal, where a Saudi blogger, Omar Abdulaziz, speaks nervously on the phone,” Darianna Cardilli writes in Documentary Magazine. “We learn that his anti-regime tweets have led first to his exile, then an attempted rendition, and lastly the imprisonment of his brothers. The documentary skillfully weaves together different narrative strands, until they coalesce: the investigation of a crime scene, a love story and a political thriller.”

Access and trust were the two biggest variables in deciding to proceed with the film, Fogel tells Cardilli:

“In order to tell this story, I needed the participation of the Turks. If they were not going to allow me access, then I’d be telling an archival story, a story that’s already in the news. To this day, none of these people — İrfan Fidan, the chief prosecutor; Abdülhamit Gül, the justice minister; Recep Kiliç, the police CSI forensic examiner; Fahrettin Altun, the president’s spokesperson — have given an interview or appeared on camera. But I knew that if I didn’t have that, it wasn’t going be the film that I wanted it to be, and I couldn’t tell the story as impactfully.”

READ MORE: ‘The Dissident’: Giving Voice to the Silenced (Documentary Magazine)

To capture footage for The Dissident, Fogel reteamed with Icarus cinematographer Jake Swantko. “Once Bryan said ‘Let’s make this,’ there wasn’t a lot of time to sit around and talk about how to make it look, because the story was still happening,” Swantko said in an interview with Terry McCarthy for American Cinematographer. “We had to go and film the interviews — with Omar in Canada, and then in Turkey. But then I thought to myself, ‘What kind of look do I want?’ I decided to go with the Red Weapon Epic 6K and Panavision Primo SL Series T1.9 primes, and make it a slightly dark thriller — which is what it was. Bryan trusts my instincts in that respect.”

“What Paul Greengrass did in the Bourne movies was a real inspiration for us,” Fogel added. “They feel so real, with huge vérité elements.”

The film features three principal interview subjects: Khashoggi’s associate, Omar Abdulaziz, who was in touch with Khashoggi just hours before he was killed; Khashoggi’s fiancée, Hatice Cengiz, who waited for hours outside the Saudi embassy in Istanbul in vain; and Irfan Fidan, the Turkish chief prosecutor who investigated the murder.

One of Swantko’s main challenges during production was evoking a sense of intimacy with the interviewees through the camera. “We aimed for a place where the subject is telling their story as an active participant, not just sitting for an interview with someone who flies in,” Swantko told McCarthy, noting that he spent considerable time blocking each interview, including two to three hours of setup time. “I told the crew that this isn’t a run-or-gun situation,´ Swantko said. “We needed bigger locations — rooms over 1,000 square feet.”

To create a dramatic look, Swantko wanted to be able to move the camera in and out on subjects’ faces, setting up a dolly on a four-foot track. There were also cameras positioned over Fogel’s shoulder and at a three-quarter angle from the shoulders up. “The dolly gave me three different shots,” the DP detailed, “a low wide close-up at the end of the rail, a medium shot in the middle, and a low medium shot at the back of the rails.”

Want more on the cinematography of The Dissident? Watch Fogel and Swantko discuss the making of the film with Buddy Squires, ASC as part of the “ASC Clubhouse Conversations” series on Vimeo: The Dissident: Writer-Director Bryan Fogel and Cinematographer Jake Swantko.

READ MORE: Documenting The Dissident (American Cinematographer)

Following on the heels of Showtime documentary Kingdom of Silence, which aired in October, The Dissident holds few new revelations, but benefits from exclusive access to Cengiz and Abdulaziz, as well as interviews with Istanbul forensic police and other Turkish officials.

“The Dissident inevitably recounts Khashoggi’s murder, but takes place largely in the present tense and you come to see how his legacy lives on as well as the threats that ultimately took his life,” Stephen Saito writes in Moveable Feast. As Fogel learned more about Khashoggi, it became clear that “this guy was a moderate,” as he recounts to Saito about his decision to make the film:

“He wasn’t a friend of ISIS or a terrorist sympathizer. Yes, he had met Bin Laden in the ‘80s, but that’s when the United States was friends with Bin Laden and I had multiple researchers who were fluent in Arabic, looking up who he was and his writings and reading his old books on top of his writings for the Washington Post. What [I learned was Khoshoggi] was a moderate who was so driven to have a freedom of speech and a freedom of opinion and saw that his country was going down the wrong path. He was willing to put himself into self-exile and risk his life to bring about some semblance of freedom of press as he saw his own government push forward their false narrative and take over Twitter and jail countless journalists and anyone who dared have a differing opinion to Mohammed bin Salman. That is what made me want to take on this film.”

READ MORE: Interview: Bryan Fogel on Bringing to Light an Invisible War in “The Dissident” (Moveable Feast)

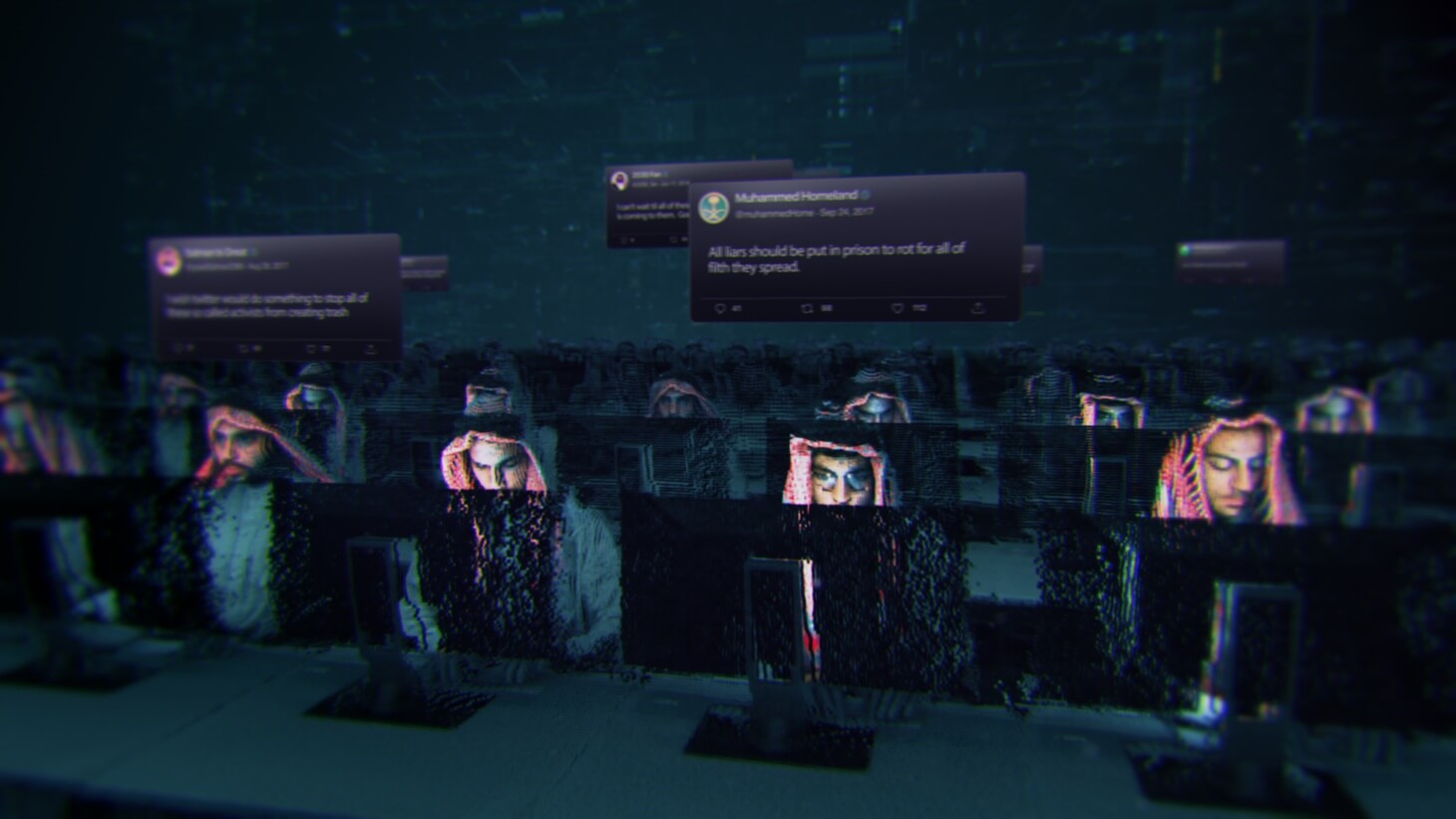

A major portion of the film is dedicated to explaining the Saudi Arabian government’s role in online surveillance and manipulation, including on Twitter, which “could be the next stage of global warfare,” as Sean Price writes in The Spool. “Fogel shows how the Crown Prince creates his own army of Twitter trolls, known as ‘The Flies,’ who manipulate the platform’s algorithms to make pro-regime posts trend while drowning out any tweets that may be critical of Salman,” Price notes. “[Omar] Abdulaziz returns the favor by creating his own army of Twitter warriors, known as ‘The Bees,’ to counter The Flies with tweets that espouse freedom of speech.”

READ MORE: “The Dissident” is a gripping look at Jamal Khashoggi’s murder (The Spool)

Fogel recounts how the royal family sought to control online messaging in Saudi Arabia in an interview with Sacha Pfeiffer for NPR, including how Khashoggi had been complicating those efforts:

“I think this is one of the major reasons why he was ultimately murdered. And this was a real concern to the old guard in that region, especially the Saudis and the Emirates that really had a hold on power. And what they realized was that if you could essentially control the public sphere on Twitter, that you could control the narrative and in controlling the narrative, essentially quash freedom of speech, stop protests and essentially protect your monarchy.

“So Saudi Arabia starts implementing a policy where they begin to hire hundreds and ultimately thousands of people and call them Twitter trolls, I guess is the best word for it. And what this means is if Jamal Khashoggi was sending out a tweet saying, I disagree with MBS on such and such — right? — the very next thing — his Twitter feed is flooded with hundreds and hundreds of comments. You’re a traitor. You’re not a real Saudi. You have no idea what you’re talking about. And so Jamal’s voice was lost as well as anybody dissenting against MBS. And the Saudi narrative is what is trending on Twitter.”

READ MORE: Film Maker Discusses New Documentary On Murdered Journalist Jamal Khashoggi (NPR)

Despite an enthusiastic reception at Sundance, every major studio and streaming service passed on the film, and Fogel initially struggled to find distribution for The Dissident. It was finally picked up by Briarcliff Entertainment for a limited theatrical engagement in December followed by a video-on-demand release in January.

“I was very disappointed by the fear and cowardice. It’s everyone — Netflix, Amazon, HBO, Hulu and all the theatrical distributors,” Fogel commented to the Los Angeles Times’ Stuart Miller. “Saudi Arabia has one of the world’s largest sovereign funds for investment and they’re the money behind SoftBank and they invest in Hollywood.”

READ MORE: Filmmaker tracks the killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in ‘The Dissident’ (Los Angeles Times)

“A film by an Oscar-winning filmmaker would normally garner plenty of attention from streaming services, which have used documentaries and niche movies to attract subscribers and earn awards,” Nicole Sperling observes in the New York Times. “Instead, when Mr. Fogel’s film, The Dissident, was finally able to find a distributor after eight months, it was with an independent company that had no streaming platform and a much narrower reach,” she writes.

“These global media companies are no longer just thinking, ‘How is this going to play for U.S. audiences?” Fogel told Sperling. “They are asking: ‘What if I put this film out in Egypt? What happens if I release it in China, Russia, Pakistan, India?’ All these factors are coming into play, and it’s getting in the way of stories like this.”